Tang dynasty

Tang 唐 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

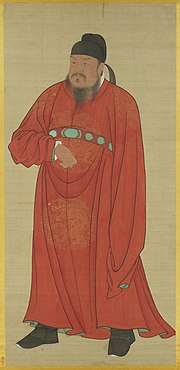

• 618–626 (first) | Emperor Gaozu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 626–649 | Emperor Taizong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 712–756 | Emperor Xuanzong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 904–907 (last) | Emperor Ai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval East Asia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| June 18, 618 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Wu Zhou interregnum | 690–705 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 755–763 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Abdication in favour of Later Liang | June 1, 907 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 715[4][5] | 5,400,000 km2 (2,100,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 7th century | 50 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 9th century | 80 million | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Cash coins | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tang dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Tang dynasty" in Han characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 唐朝 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Tángcháo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

The Tang dynasty (/tɑːŋ/,[6] [tʰǎŋ]; Chinese: 唐朝[a]), or the Tang Empire, was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907, with an interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed by the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Historians generally regard the Tang as a high point in Chinese civilisation, and a golden age of cosmopolitan culture.[8] Tang territory, acquired through the military campaigns of its early rulers, rivalled that of the Han dynasty.

The Li family founded the dynasty after taking advantage of a period of Sui decline and precipitating their final collapse, in turn inaugurating a period of progress and stability in the first half of the dynasty's rule. The dynasty was formally interrupted during 690–705 when Empress Wu Zetian seized the throne, proclaiming the Wu Zhou dynasty and becoming the only legitimate Chinese empress regnant. The An Lushan rebellion (755–763) led to devastation and the decline of central authority during the latter half of the the dynasty. Like the previous Sui dynasty, the Tang maintained a civil-service system by recruiting scholar-officials through standardised examinations and recommendations to office. The rise of regional military governors known as jiedushi during the 9th century undermined this civil order. The dynasty and central government went into decline by the latter half of the 9th century; agrarian rebellions resulted in mass population loss and displacement, widespread poverty, and further government dysfunction that ultimately ended the dynasty in 907.

The Tang capital at Chang'an (present-day Xi'an) was the world's most populous city for much of the dynasty's existence. Two censuses of the 7th and 8th centuries estimated the empire's population at about 50 million people,[9][10] which grew to an estimated 80 million by the dynasty's end.[11][12][b] From its numerous subjects, the dynasty raised professional and conscripted armies of hundreds of thousands of troops to contend with nomadic powers for control of Inner Asia and the lucrative trade-routes along the Silk Road. Far-flung kingdoms and states paid tribute to the Tang court, while the Tang also indirectly controlled several regions through a protectorate system. In addition to its political hegemony, the Tang exerted a powerful cultural influence over neighbouring East Asian nations such as Japan and Korea.

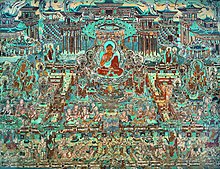

Chinese culture flourished and further matured during the Tang era. It is traditionally considered the greatest age for Chinese poetry.[13] Two of China's most famous poets, Li Bai and Du Fu, belonged to this age, contributing with poets such as Wang Wei to the monumental Three Hundred Tang Poems. Many famous painters such as Han Gan, Zhang Xuan, and Zhou Fang were active, while Chinese court music flourished with instruments such as the popular pipa. Tang scholars compiled a rich variety of historical literature, as well as encyclopaedias and geographical works. Notable innovations included the development of woodblock printing. Buddhism became a major influence in Chinese culture, with native Chinese sects gaining prominence. However, in the 840s, Emperor Wuzong enacted policies to suppress Buddhism, which subsequently declined in influence.

History

Establishment

The Li family had ethnic Han origins, and it belonged to the northwest military aristocracy prevalent during the Sui dynasty.[14][15] According to official Tang records, they were paternally descended from Laozi, the traditional founder of Taoism (whose personal name was Li Dan or Li Er), the Han dynasty general Li Guang, and Li Gao, the founder of the Han-ruled Western Liang kingdom.[16][17][18] This family was known as the Longxi Li lineage, and it included the prominent Tang poet Li Bai. Aside from traditional historiography, some modern historians have suggested that the Tang imperial family might have modified its genealogy to conceal Xianbei heritage.[19][20] The Tang emperors had part-Xianbei maternal ancestry, from Emperor Gaozu of Tang's part-Xianbei mother, Duchess Dugu.[21][22]

Li Yuan, the founder of the Tang dynasty, was Duke of Tang and governor of Taiyuan, the capital of modern Shanxi, during the collapse of the Sui dynasty.[14][24] He had prestige and military experience, and was a first cousin of Emperor Yang of Sui (their mothers were both one of the Dugu sisters).[9] Li Yuan rose in rebellion in 617, along with his son and his equally militant daughter Princess Pingyang (d. 623), who raised and commanded her own troops. In winter 617, Li Yuan occupied Chang'an, relegated Emperor Yang to the position of Taishang Huang or retired emperor, and acted as regent to the puppet child-emperor, Yang You.[25] On the news of Emperor Yang's murder by General Yuwen Huaji on June 18, 618, Li Yuan declared himself the emperor of a new dynasty, the Tang.[25][26]

Li Yuan, known as Emperor Gaozu of Tang, ruled until 626, when he was forcefully deposed by his son Li Shimin, the Prince of Qin. Li Shimin had commanded troops since the age of 18, had prowess with bow and arrow, sword and lance and was known for his effective cavalry charges.[9][27] Fighting a numerically superior army, he defeated Dou Jiande (573–621) at Luoyang in the Battle of Hulao on May 28, 621.[28][29] Due to fear of assassination, Li Shimin ambushed and killed two of his brothers, Li Yuanji (b. 603) and crown prince Li Jiancheng (b. 589), in the Xuanwu Gate Incident on July 2, 626.[30] Shortly thereafter, his father abdicated in his favour, and Li Shimin ascended the throne. He is conventionally known by his temple name Taizong.[9]

Although killing two brothers and deposing his father contradicted the Confucian value of filial piety,[30] Taizong showed himself to be a capable leader who listened to the advice of the wisest members of his council.[9] In 628, Emperor Taizong held a Buddhist memorial service for the casualties of war; in 629, he had Buddhist monasteries erected at the sites of major battles so that monks could pray for the fallen on both sides of the fight.[31]

During the Tang campaign against the Eastern Turks, the Eastern Turkic Khaganate was destroyed after the capture of its ruler, Illig Qaghan by the famed Tang military officer Li Jing (571–649), who later became a Chancellor of the Tang dynasty. With this victory, the Turks accepted Taizong as their khagan, a title rendered as Tian Kehan in addition to his rule as emperor of China under the traditional title "Son of Heaven".[32][33] Taizong was succeeded by his son Li Zhi (as Emperor Gaozong) in 649.

The Tang dynasty further led the Tang campaigns against the Western Turks. Early military conflicts were a result of the Tang interventions in the rivalry between the Western and Eastern Turks in order to weaken both. Under Emperor Taizong, campaigns were dispatched in the Western Regions against Gaochang in 640, Karasahr in 644 and 648, and Kucha in 648. The wars against the Western Turks continued under Emperor Gaozong, and the Western Turkic Khaganate was finally annexed after General Su Dingfang's defeat of Khagan Ashina Helu in 657.

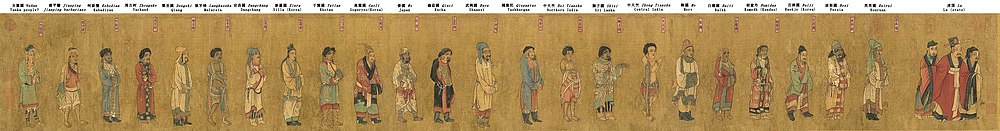

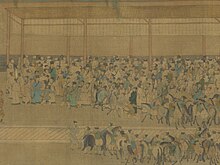

Around that time, the Tang court enjoyed the visit of numerous dignitaries from foreign lands. These were portraited in Portraits of Periodical Offering, probably painted by Yan Liben (601–673).[34] From right to left are representatives hailing from Lu (魯國)—a reference to the Eastern Wei—Rouran (芮芮國), Persia (波斯國), Baekje (百濟國), Kumedh (胡密丹), Baiti (白題國), Mohe people (靺國), Central India (中天竺), Sri Lanka (獅子國), Northern India (北天竺), Tashkurgan (謁盤陀), Wuxing of the Chouchi ((武興國), Kucha ((龜茲國), Japan (倭國), Goguryeo (高麗國), Khotan (于闐國), Silla (新羅國), Dangchang (宕昌國), Langkasuka (狼牙修), Dengzhi (鄧至國), Yarkand (周古柯), Kabadiyan (阿跋檀), the "Barbarians of Jianping" (建平蠻), and Nudan (女蜑國).

Wu Zetian's usurpation

Although she entered Emperor Gaozong's court as the lowly consort, Wu Zetian rose to the highest seat of power in 690, establishing the short-lived Wu Zhou. Empress Wu's rise to power was achieved through cruel and calculating tactics: a popular conspiracy theory stated that she killed her own baby girl and blamed it on Gaozong's empress so that the empress would be demoted.[35] Emperor Gaozong suffered a stroke in 655, and Wu began to make many of his court decisions for him, discussing affairs of state with his councillors, who took orders from her while she sat behind a screen.[36] When Empress Wu's eldest son, the crown prince, began to assert his authority and advocate policies opposed by Empress Wu, he suddenly died in 675. Many suspected he was poisoned by Empress Wu. Although the next heir apparent kept a lower profile, he was accused by Wu in 680 of plotting a rebellion; he was banished and later obliged to commit suicide.[37]

In 683, Emperor Gaozong died, and was succeeded by Emperor Zhongzong, his eldest surviving son by Wu. Zhongzong tried to appoint his wife's father as chancellor: after only six weeks on the throne, he was deposed by Empress Wu in favour of his younger brother, Emperor Ruizong.[37] This provoked a group of Tang princes to rebel in 684. Wu's armies suppressed them within two months.[37] She proclaimed the Tianshou era of Wu Zhou on October 16, 690,[38] and three days later demoted Emperor Ruizong to crown prince.[39] He was also forced to give up his father's surname Li in favour of the Empress Wu.[39] She then ruled as China's only empress regnant.

A palace coup on February 20, 705, forced Empress Wu to yield her position on February 22. The next day, her son Zhongzong was restored to power; the Tang was formally restored on March 3. She died soon after.[41] To legitimise her rule, she circulated a document known as the Great Cloud Sutra, which predicted that a reincarnation of the Maitreya Buddha would be a female monarch who would dispel illness, worry, and disaster from the world.[42][43] She even introduced numerous revised written characters for the language, though they reverted to the original forms after her death.[44] Arguably the most important part of her legacy was diminishing the hegemony of the Northwestern aristocracy, allowing people from other clans and regions of China to become more represented in Chinese politics and government.[45][46]

Emperor Xuanzong's reign

There were many prominent women at court during and after Wu's reign, including Shangguan Wan'er (664–710), a poet, writer, and trusted official in charge of Wu's private office.[48] In 706, the wife of Emperor Zhongzong of Tang, Empress Wei (d. 710), persuaded her husband to staff government offices with his sister and her daughters, and in 709 requested that he grant women the right to bequeath hereditary privileges to their sons (which before was a male right only).[49] Empress Wei eventually poisoned Zhongzong, whereupon she placed his fifteen-year-old son upon the throne in 710. Two weeks later, Li Longji (the later Emperor Xuanzong) entered the palace with a few followers and slew Empress Wei and her faction. He then installed his father Emperor Ruizong (r. 710–712) on the throne.[50] Just as Emperor Zhongzong was dominated by Empress Wei, so too was Ruizong dominated by Princess Taiping.[51] This ended when Princess Taiping's coup failed in 712, and Emperor Ruizong abdicated to Emperor Xuanzong.[50][49]

During the 44-year reign of Emperor Xuanzong, the Tang dynasty reached its height, a golden age with low economic inflation and a toned down lifestyle for the imperial court.[52][46] Seen as a progressive and benevolent ruler, Xuanzong abolished the death penalty in 747; all executions had to be approved beforehand by the emperor—there were only 24 executions in 730.[53] Xuanzong bowed to the consensus of his ministers on policy decisions and made efforts to staff government ministries fairly with different political factions.[51] His staunch Confucian chancellor Zhang Jiuling (673–740) worked to reduce deflation and increase the money supply by upholding the use of private coinage, while his aristocratic and technocratic successor Li Linfu (d. 753) favoured government monopoly over the issuance of coinage.[54] After 737, most of Xuanzong's confidence rested in his long-standing chancellor Li Linfu, who championed a more aggressive foreign policy employing non-Chinese generals. This policy ultimately created the conditions for a massive rebellion against Xuanzong.[55]

An Lushan rebellion and catastrophe

The Tang Empire was at its height of power up until the middle of the 8th century, when the An Lushan rebellion (755–763) destroyed the prosperity of the empire. An Lushan was a half-Sogdian, half-Turkic Tang commander since 744, who had experience fighting the Khitans of Manchuria with a victory in 744, yet most of his campaigns against the Khitans were unsuccessful.[56] He was given great responsibility in Hebei, which allowed him to rebel with an army of more than 100,000 troops. After capturing Luoyang, he named himself emperor of a new, but short-lived, Yan state. Despite early victories scored by the Tang general Guo Ziyi (697–781), the newly recruited troops of the army at the capital were no match for An Lushan's frontier veterans; the court fled Chang'an. While the heir apparent raised troops in Shanxi and Xuanzong fled to Sichuan, they called upon the help of the Uyghur Khaganate in 756. The Uyghur khan Moyanchur was greatly excited at this prospect, and married his own daughter to the Chinese diplomatic envoy once he arrived, receiving in turn a Chinese princess as his bride. The Uyghurs helped recapture the Tang capital from the rebels, but they refused to leave until the Tang paid them an enormous sum of tribute in silk. Even Abbasid Arabs assisted the Tang in putting down the rebellion.[57][58][59] A massacre of foreign Arab and Persian Muslim merchants by Tian Shengong happened during the An Lushan rebellion in the 760 Yangzhou massacre.[60][61] The Tibetans took hold of the opportunity and raided many areas under Chinese control, and even after the Tibetan Empire had fallen apart in 842, followed soon after by the Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho, the Tang were in no position to reconquer Central Asia after 763.[57][62] So significant was this loss that half a century later jinshi examination candidates were required to write an essay on the causes of the Tang's decline.[63] Although An Lushan was killed by one of his eunuchs in 757, this time of troubles and widespread insurrection continued until rebel Shi Siming was killed by his own son in 763.[64]

After 710, regional military governors called jiedushi gradually came to challenge the power of the central government.[65] After the An Lushan rebellion, the autonomous power and authority accumulated by the jiedushi in Hebei went beyond the central government's control. After a series of rebellions between 781 and 784 in present-day Hebei, Henan, Shandong, and Hubei, the government had to officially acknowledge the jiedushi's hereditary rule without accreditation. The Tang government relied on these governors and their armies for protection and to suppress local revolts. In return, the central government would acknowledge the rights of these governors to maintain their army, collect taxes and even to pass on their title to heirs.[66] As time passed, these military governors slowly phased out the prominence of civil officials drafted by exams, and became more autonomous from central authority. The rule of these powerful military governors lasted until 960, when a new civil order under the Song dynasty was established. The abandonment of the equal-field system also meant that people could buy and sell land freely; many poor fell into debt because of this and were forced to sell their land to the wealthy, which led to the exponential growth of large estates.[57] With the breakdown of the land allocation system after 755, the central Chinese state barely interfered in agricultural management and acted merely as tax collector for roughly a millennium, save a few instances such as the Song's failed land nationalisation during the 13th-century war with the Mongols.[67]

With the central government collapsing in authority over the various regions of the empire, it was recorded in 845 that bandits and river pirates in parties of 100 or more began plundering settlements along the Yangtze River with little resistance. In 858, massive floods along the Grand Canal inundated vast tracts of land and terrain of the North China Plain, which drowned tens of thousands of people in the process. The Chinese belief in the Mandate of Heaven granted to the ailing Tang was also challenged when natural disasters led many to believe that the Tang had lost their right to rule. In 873, a disastrous harvest shook the foundations of the empire; in some areas only half of all agricultural produce was gathered, and tens of thousands faced famine and starvation. In the earlier period of the Tang, the central government was able to meet crises in the harvest—from 714 to 719, records show that the Tang government responded effectively to natural disasters by extending the price-regulation granary system throughout the country. The central government was able then to build a large surplus stock of foods to ward off the rising danger of famine and increased agricultural productivity through land reclamation.[52][68]

Rebuilding and recovery

Although these natural calamities and rebellions stained the reputation and hampered the effectiveness of the central government, the early 9th century is nonetheless viewed as a period of recovery for the Tang.[69] The government's withdrawal from its role in managing the economy had the unintended effect of stimulating trade, as more markets with fewer bureaucratic restrictions were opened up.[70][71] By 780, the old grain tax and labour service of the 7th century was replaced by a semi-annual tax paid in cash, signifying the shift to a money economy boosted by the merchant class.[59] Cities in the southern Jiangnan region such as Yangzhou, Suzhou, and Hangzhou prospered the most economically during the late Tang period.[70] The government monopoly on salt production, weakened after the An Lushan rebellion, was placed under the Salt Commission, which became one of the most powerful state agencies, run by capable ministers chosen as specialists. The commission began the practice of selling merchants the rights to buy monopoly salt, which they transported and sold in local markets. In 799, salt accounted for over half of the government's revenues.[57] S. A. M. Adshead writes that this salt tax represents "the first time that an indirect tax, rather than tribute, levies on land or people, or profit from state enterprises such as mines, had been the primary resource of a major state".[72] Even after the power of the central government was in decline after the mid-8th century, it was still able to function and give out imperial orders on a massive scale. The Old Book of Tang (945) recorded that a government decree issued in 828 standardised the use of square-pallet chain pumps for irrigation throughout the country.{sfn|Needham|1986b|p=347}}

The last ambitious ruler of the Tang was Emperor Xianzong (r. 805–820), whose reign was aided by the fiscal reforms of the 780s, including a government monopoly on the salt industry. He also had an effective and well-trained imperial army stationed at the capital led by his court eunuchs; this was the Army of Divine Strategy, numbering 240,000 in strength as recorded in 798. Between 806 and 819, Emperor Xianzong conducted seven major military campaigns to quell the rebellious provinces that had claimed autonomy from central authority, managing to subdue all but two of them. Under his reign, there was a brief end to the hereditary jiedushi, as Xianzong appointed his own military officers and staffed the regional bureaucracies once again with civil officials.[73] However, Xianzong's successors proved less capable and more interested in the leisure of hunting, feasting, and playing outdoor sports, allowing eunuchs to amass more power as drafted scholar-officials caused strife in the bureaucracy with factional parties.[74] The eunuchs' power was not challenged following the Ganlu Incident, where Emperor Wenzong (r. 826–840) failed in his plot to have them overthrown; instead, Wenzong's allies were publicly executed in Chang'an's West Market on the eunuchs' command.[70]

Decades after the An Lushan rebellion, the Tang was able to muster enough power to launch offensive military campaigns, including its destruction of the Uyghur Khaganate in Mongolia from 840 to 847.[75] The Tang managed to restore indirect control over former territories as far west as the Hexi Corridor and Dunhuang in Gansu; in 848, the general Zhang Yichao (799–872) managed to wrestle control of the region from the Tibetan Empire during its civil war.[76] Shortly afterwards, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (r. 846–859) acknowledged Zhang as the protector (防禦使; fángyùshǐ) of Sha Prefecture, and military governor of the new Guiyi Circuit.[77]

End of the dynasty

In addition to factors like natural calamity and jiedushi claiming autonomy, a rebellion by Huang Chao (874–884) devastated both northern and southern China, took an entire decade to suppress, resulted in the sacking of both Chang'an and Luoyang.[78] In 878–879, Huang's army committed a massacre in the southern port of Guangzhou against foreign Arab and Persian Muslim, Zoroastrian, Jewish and Christian merchants.[79] A medieval Chinese source claimed that Huang Chao killed 8 million people.[80] The Tang never recovered from Huang's rebellion, which paved the way for the later overthrow of the Tang. Large groups of bandits in the size of small armies ravaged the countryside in the last years of the Tang. They smuggled illicit salt, ambushed merchants and convoys, and even besieged several walled cities.[81] Amid the sacking of cities and murderous factional strife among eunuchs and officials, the top tier of aristocratic families, which had amassed a large fraction of the landed wealth and official positions, was largely destroyed or marginalised.[82][83]

During the last two decades of the Tang dynasty, the gradual collapse of central authority led to the rise of the rival military figures Li Keyong and Zhu Wen in northern China.[84] Tang forces had defeated Huang's rebellion with the aid of allied Shatuo, a Turkic people of what is now Shanxi, led by Li Keyong. He was made a jiedushi, and later Prince of Jin, bestowed with the imperial surname Li by the Tang court.[85] Zhu Wen, originally a salt smuggler who served as a lieutenant under the rebel Huang Chao, surrendered to Tang forces. By helping to defeat Huang, he was renamed Zhu Quanzhong ("Zhu of Perfect Loyalty") and granted a rapid series of promotions to military governor of Xuanwu Circuit.[86][87]

In 901, from his power base of Kaifeng, Zhu Wen seized control of the Tang capital Chang'an and with it the imperial family.[88] By 903, he forced Emperor Zhaozong of Tang to move the capital to Luoyang, preparing to take the throne for himself. In 904, Zhu assassinated Emperor Zhaozong to replace him with the emperor's young son Emperor Ai of Tang. In 905, Zhu executed the brothers of Emperor Ai as well as many officials and Empress Dowager He. In 907, the Tang dynasty was ended when Zhu deposed Ai and took the throne for himself (known posthumously as Emperor Taizu of Later Liang). He established the Later Liang, which inaugurated the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. A year later Zhu had the deposed Emperor Ai poisoned to death.[86]

Zhu Wen's enemy Li Keyong died in 908, having never claimed the title of emperor out of loyalty to the Tang. His son Li Cunxu (Emperor Zhuangzong) inherited his title Prince of Jin along with his father's rivalry against Zhu. In 923, Li Cunxu declared a "restored" Tang dynasty, the Later Tang, before toppling the Later Liang dynasty the same year. However, southern China remained splintered into various small kingdoms until most of China was reunified under the Song dynasty (960–1279). Control over parts of northeast China and Manchuria by the Liao dynasty of the Khitan people also stemmed from this period. In 905, their leader Abaoji formed a military alliance with Li Keyong against Zhu Wen but the Khitans eventually turned against the Later Tang, helping another Shatuo leader Shi Jingtang of Later Jin to overthrow Later Tang in 936.[89]

Administration and politics

Initial reforms

Taizong set out to solve internal problems within the government which had constantly plagued past dynasties. Building upon the Sui legal code, he issued a new legal code that subsequent Chinese dynasties would model theirs upon, as well as neighbouring polities in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan.[9] The earliest law code to survive was established in 653; it was divided into 500 articles specifying different crimes and penalties ranging from ten blows with a light stick, one hundred blows with a heavy rod, exile, penal servitude, or execution. The legal code distinguished different levels of severity in meted punishments when different members of the social and political hierarchy committed the same crime. For example, the severity of punishment was different when a servant or nephew killed a master or an uncle than when a master or uncle killed a servant or nephew.[90]

The Tang Code was largely retained by later codes such as the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644) code of 1397,[91] yet there were several revisions in later times, such as improved property rights for women during the Song dynasty (960–1279).[92][93]

The Tang had three departments (省; shěng), which were obliged to draft, review, and implement policies respectively. There were also six ministries (部; bù) under the administrations that implemented policy, each of which was assigned different tasks. These Three Departments and Six Ministries included the personnel administration, finance, rites, military, justice, and public works—an administrative model which lasted until the fall of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912).[94]

Although the founders of the Tang related to the glory of the earlier Han dynasty (3rd century BC – 3rd century AD), the basis for much of their administrative organisation was very similar to the previous Northern and Southern dynasties. The Northern Zhou (6th century) fubing system of divisional militia was continued by the Tang, along with farmer-soldiers serving in rotation from the capital or frontier in order to receive appropriated farmland. The equal-field system of the Northern Wei (4th–6th centuries) was also kept, although there were a few modifications.[9]

Although the central and local governments kept an enormous number of records about land property in order to assess taxes, it became common practice in the Tang for literate and affluent people to create their own private documents and signed contracts. These had their own signature and that of a witness and scribe in order to prove in court (if necessary) that their claim to property was legitimate. The prototype of this actually existed since the ancient Han dynasty, while contractual language became even more common and embedded into Chinese literary culture in later dynasties.[95]

The centre of the political power of the Tang was the capital city of Chang'an (modern Xi'an), where the emperor maintained his large palace quarters and entertained political emissaries with music, sports, acrobats, poetry, paintings, and dramatic theatre performances. The capital was also filled with incredible amounts of riches and resources to spare. When the Chinese prefectural government officials travelled to the capital in 643 to give the annual report of the affairs in their districts, Emperor Taizong discovered that many had no proper quarters to rest in and were renting rooms with merchants. Therefore, Emperor Taizong ordered the government agencies in charge of municipal construction to build every visiting official his own private mansion in the capital.[96]

Imperial examinations

Students of Confucian studies were candidates for the imperial examinations, which qualified their graduates for appointment to the local, provincial, and central government bureaucracies. Two types of exams were given, mingjing (明經; 'illuminating the classics') and jinshi (進士; 'presented scholar'). The mingjing was based upon the Confucian classics and tested the student's knowledge of a broad variety of texts. The jinshi tested a student's literary abilities in writing essays in response to questions on governance and politics, as well as in composing poetry.[97] Candidates were also judged on proper deportment, appearance, speech, and calligraphy, all subjective criteria that favoured the wealthy over those of more modest means who were unable to pay tutors of rhetoric and writing.Although a disproportionate number of civil officials came from aristocratic families, wealth and noble status were not prerequisites, and the exams were open to all male subjects whose fathers were not of the artisan or merchant classes.[98][35] To promote widespread Confucian education, the Tang government established state-run schools and issued standard versions of the Five Classics with commentaries.[99]

Open competition was designed to draw the best talent into government. But perhaps an even greater consideration for the Tang rulers was to avoid imperial dependence on powerful aristocratic families and warlords by recruiting a body of career officials having no family or local power base. The Tang law code ensured equal division of inherited property among legitimate heirs, encouraging social mobility by preventing powerful families from becoming landed nobility through primogeniture.[100] The competition system proved successful, as scholar-officials acquired status in their local communities while developing an esprit de corps that connected them to the imperial court. From Tang times until the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912, scholar-officials served as intermediaries between the people and the government. The potential of a widespread examination system was not fully realised until the succeeding Song dynasty, when the merit-driven scholar official largely shed his aristocratic habits and defined his social status through the examination system.[101][102][103]

The examination system, used only on a small scale in Sui and Tang times, played a central role in the fashioning of this new elite. The early Song emperors, concerned above all to avoid domination of the government by military men, greatly expanded the civil service examination system and the government school system.[104]

Religion and politics

From the outset, religion played a role in Tang politics. In his bid for power, Li Yuan had attracted a following by claiming descent from the Taoist sage Laozi (fl. 6th century BC).[105] People bidding for office would request the prayers of Buddhist monks, with successful aspirants making donations in return. Before the persecution of Buddhism in the 9th century, Buddhism and Taoism were both accepted. Religion was central in the reign of Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–756). The Emperor invited Taoist and Buddhist monks and clerics to his court, exalted Laozi with grand titles, wrote commentary on Taoist scriptures, and set up a school to prepare candidates for Taoist examinations. In 726, he called upon the Indian monk Vajrabodhi (671–741) to perform tantric rites to avert a drought. In 742, he personally held the incense burner while patriarch of the Shingon school Amoghavajra (705–774) recited "mystical incantations to secure the victory of Tang forces".[50]

Emperor Xuanzong closely regulated religious finances. Near the beginning of his reign in 713, he liquidated the Inexhaustible Treasury of a prominent Buddhist monastery in Chang'an which had collected vast riches as multitudes of anonymous repentants left money, silk, and treasure at its doors. Although the monastery used its funds generously, the Emperor condemned it for fraudulent banking practices, and distributed its wealth to other Buddhist and Taoist monasteries, and to repair local statues, halls, and bridges.[106] In 714, he forbade Chang'an shops from selling copied Buddhist sutras, giving a monopoly of this trade to the Buddhist clergy.[107]

Taxes and the census

The Tang government attempted to create an accurate census of the empire's population, mostly for effective taxation and military conscription. The early Tang government established modest grain and cloth taxes on each household, persuading households to register and provide the government with accurate demographic information.[9] In the official census of 609, the population was tallied at 9 million households, about 50 million people,[9] and this number did not increase in the census of 742.[108] Patricia Ebrey writes that nonwithstanding census undercounting, China's population had not grown significantly since the earlier Han dynasty, which recorded 58 million people in 2 AD.[9][109] Adshead disagrees, estimating about 75 million people by 750.[110]

In the Tang census of 754, there were 1,859 cities, 321 prefectures, and 1,538 counties throughout the empire.[111] Although there were many large and prominent cities, the rural and agrarian areas comprised 80–90% of the population.[112] There was also a dramatic migration from northern to southern China, as the North held 75% of the overall population at the dynasty's inception, which by its end was reduced to 50%.[113] The Chinese population would not dramatically increase until the Song dynasty, when it doubled to 100 million because of extensive rice cultivation in central and southern China, coupled with higher yields of grain sold in a growing market.[114]

Military and foreign policy

Protectorates and tributaries

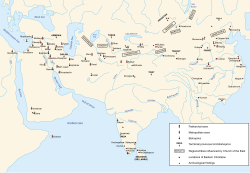

The 7th and first half of the 8th century are generally considered to be the era in which the Tang reached the zenith of its power. In this period, Tang control extended further west than any previous dynasty, stretching from north Vietnam in the south, to a point north of Kashmir bordering Persia in the west, to northern Korea in the north-east.[115]

Some of the kingdoms paying tribute to the Tang dynasty included Kashmir, Nepal, Khotan, Kucha, Kashgar, Silla, Champa, and kingdoms located in Amu Darya and Syr Darya valley.[116][117] Turkic nomads addressed the Tang emperor as Tian Kehan.[33] After the widespread Göktürk revolt of Shabolüe Khan (d. 658) was put down at Issyk Kul in 657 by Su Dingfang (591–667), Emperor Gaozong established several protectorates governed by a Protectorate General or Grand Protectorate General, which extended the Chinese sphere of influence as far as Herat in Western Afghanistan.[118] Protectorate Generals were given a great deal of autonomy to handle local crises without waiting for central admission. After Xuanzong's reign, jiedushi were given enormous power, including the ability to maintain their own armies, collect taxes, and pass their titles on hereditarily. This is commonly recognised as the beginning of the fall of Tang's central government.[57][65]

Soldiers and conscription

By 737, Emperor Xuanzong discarded the policy of conscripting soldiers that were replaced every three years, replacing them with long-service soldiers who were more battle-hardened and efficient. It was more economically feasible as well, since training new recruits and sending them out to the frontier every three years drained the treasury.[119] By the late 7th century, the fubing troops began abandoning military service and the homes provided to them in the equal-field system. The supposed standard of 100 mu of land allotted to each family was in fact decreasing in size in places where population expanded and the wealthy bought up most of the land. Hard-pressed peasants and vagrants were then induced into military service with benefits of exemption from both taxation and corvée labour service, as well as provisions for farmland and dwellings for dependents who accompanied soldiers on the frontier.[120] By 742, the total number of enlisted troops in the Tang armies had risen to about 500,000 men.[119]

Eastern regions

In East Asia, Tang military campaigns were less successful elsewhere than in previous imperial Chinese dynasties. Like the emperors of the Sui dynasty before him, Taizong established a military campaign in 644 against the Korean kingdom of Goguryeo in the Goguryeo–Tang War; however, this led to its withdrawal in the first campaign because they failed to overcome the successful defence led by General Yeon Gaesomun. The Tang entered into the Silla–Tang alliance, the Chinese fought against Baekje and their Yamato Japanese allies in the Battle of Baekgang in August 663, a decisive Tang–Silla victory. The Tang dynasty navy had several different ship types at its disposal to engage in naval warfare, these ships described by Li Quan in his Taipai Yinjing (Canon of the White and Gloomy Planet of War) of 759.[121] The Battle of Baekgang was actually a restoration movement by remnant forces of Baekje, since their kingdom was toppled in 660 by a Tang–Silla invasion, led by Chinese general Su Dingfang and Korean general Kim Yushin (595–673). In another joint invasion with Silla, the Tang army severely weakened the Goguryeo Kingdom in the north by taking out its outer forts in 645. With joint attacks by Silla and Tang armies under commander Li Shiji (594–669), the Kingdom of Goguryeo was destroyed by 668.[122]

Although they were formerly enemies, the Tang accepted officials and generals of Goguryeo into their administration and military, such as the brothers Yeon Namsaeng (634–679) and Yeon Namsan (639–701). From 668 to 676, the Tang Empire controlled northern Korea. However, Silla broke the alliance in 671, and began the Silla–Tang War to expel the Tang forces. At the same time the Tang faced threats on its western border when a large Chinese army was defeated by the Tibetans on the Dafei River in 670. By 676, the Tang army was expelled out of Korea by a unified Silla.[123] Following a revolt of the Eastern Turks in 679, the Tang abandoned its Korean campaigns.[124]

Although the Tang had fought the Japanese, they still held cordial relations with Japan. There were numerous Imperial embassies to China from Japan, diplomatic missions that were not halted until 894 by Emperor Uda (r. 887–897), upon persuasion by Sugawara no Michizane (845–903).[125] The Japanese Emperor Tenmu (r. 672–686) even established his conscripted army on that of the Chinese model, based his state ceremonies on the Chinese model, and constructed his palace at Fujiwara on the Chinese model of architecture.[126]

Many Chinese Buddhist monks came to Japan to help further the spread of Buddhism as well. Two 7th-century monks, Zhi Yu and Zhi You, visited the court of Emperor Tenji (r. 661–672), whereupon they presented a gift of a south-pointing chariot that they had crafted.[127] This vehicle employing a differential gear was reproduced in several models for Tenji in 666, as recorded in the Nihon Shoki (720).[127] Japanese monks also visited China; such was the case with Ennin (794–864), who wrote of his travel experiences including travels along the Grand Canal.[128][129] The Japanese monk Enchin (814–891) stayed in China from 839 to 847, and again from 853 to 858, landing near Fuzhou, Fujian and setting sail for Japan from Taizhou, Zhejiang during his second trip to China.[130][73]

Western and Northern regions

The Sui and Tang carried out successful military campaigns against the steppe nomads. Chinese foreign policy to the north and west now had to deal with Turkic nomads, who were becoming the most dominant ethnic group in Central Asia.[131][132] To handle and avoid any threats posed by the Turks, the Sui government repaired fortifications and received their trade and tribute missions.[133] They sent four royal princesses to form heqin marriage alliances with Turkic clan leaders, in 597, 599, 614, and 617. The Sui stirred trouble and conflict among ethnic groups against the Turks.[134][135] As early as the Sui dynasty, the Turks had become a major militarised force employed by the Chinese. When the Khitans began raiding northeast China in 605, a Chinese general led 20,000 Turks against them, distributing Khitan livestock and women to the Turks as a reward.[136] On two occasions between 635 and 636, Tang royal princesses were married to Turk mercenaries or generals in Chinese service.[135] Throughout the Tang dynasty until the end of 755, there were approximately ten Turkic generals serving under the Tang.[137][138] While most of the Tang army was made of fubing Chinese conscripts, the majority of the troops led by Turkic generals were of non-Chinese origin, campaigning largely in the western frontier where the presence of fubing troops was low.[139] Some "Turkic" troops were tribalised Han Chinese, a desinicised people.[140]

Civil war in China was almost totally diminished by 626, along with the 628 defeat of the Ordos warlord Liang Shidu; after these internal conflicts, the Tang began an offensive against the Turks.[141] In 630, Tang armies captured areas of the Ordos Desert, modern-day Inner Mongolia province, and southern Mongolia from the Turks.[136][142] After this military victory, On June 11, 631, Emperor Taizong also sent envoys to the Xueyantuo bearing gold and silk in order to persuade the release of enslaved Chinese prisoners who were captured during the transition from Sui to Tang from the northern frontier; this embassy succeeded in freeing 80,000 Chinese men and women who were then returned to China.[143][144]

While the Turks were settled in the Ordos region (former territory of the Xiongnu), the Tang government took on the military policy of dominating the central steppe. As during the earlier Han dynasty, the Tang and their Turkic allies conquered and subdued Central Asia during the 640s and 650s.[133] During Emperor Taizong's reign alone, large campaigns were launched against not only the Göktürks, but also separate campaigns against the Tuyuhun, the oasis states, and the Xueyantuo. Under Emperor Gaozong, a campaign led by the general Su Dingfang was launched against the Western Turks ruled by Ashina Helu.[145]

The Tang Empire competed with the Tibetan Empire for control of areas in Inner and Central Asia, which was at times settled with marriage alliances such as the marrying of Princess Wencheng (d. 680) to Songtsän Gampo (d. 649).[146][147] A Tibetan tradition mentions that Chinese troops captured Lhasa after Songtsän Gampo's death,[148] but no such invasion is mentioned in either Chinese annals or the Tibetan manuscripts of Dunhuang.[149]

There was a string of conflicts with Tibet over territories in the Tarim Basin between 670 and 692; in 763, the Tibetans captured Chang'an for fifteen days during the An Lushan rebellion.[150][151] In fact, it was during this rebellion that the Tang withdrew its western garrisons stationed in what is now Gansu and Qinghai, which the Tibetans then occupied along with the territory of what is now Xinjiang.[152] Hostilities between the Tang and Tibet continued until they signed the Changqing Treaty in 821.[153] The terms of this treaty, including the fixed borders between the two countries, are recorded in a bilingual inscription on a stone pillar outside the Jokhang temple in Lhasa.[154]

During the Islamic conquest of Persia (633–656), the son of the last ruler of the Sasanian Empire, Prince Peroz and his court moved to Tang China.[116][155] According to the Old Book of Tang, Peroz was made the head of a Governorate of Persia in present-day Zaranj, Afghanistan. During this conquest of Persia, the Rashidun Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656) sent an embassy to the Tang court at Chang'an.[138] Arab sources claim Umayyad commander Qutayba ibn Muslim briefly took Kashgar from China and withdrew after an agreement,[156] but modern historians entirely dismiss this claim.[157][158][159] The Arab Umayyad Caliphate in 715 deposed Ikhshid, the king the Fergana Valley, and installed a new king Alutar on the throne. The deposed king fled to Kucha (seat of Anxi Protectorate), and sought Chinese intervention. The Chinese sent 10,000 troops under Zhang Xiaosong to Ferghana. He defeated Alutar and the Arab occupation force at Namangan and reinstalled Ikhshid on the throne.[160] The Tang defeated the Arab Umayyad invaders at the Battle of Aksu (717). The Arab Umayyad commander Al-Yashkuri and his army fled to Tashkent after they were defeated.[161] The Turgesh then crushed the Arab Umayyads and drove them out. By the 740s, the Arabs under the Abbasid Caliphate in Khorasan had reestablished a presence in the Ferghana basin and in Sogdiana. At the Battle of Talas in 751, Karluk mercenaries under the Chinese defected, helping the Arab armies of the Caliphate to defeat the Tang force under commander Gao Xianzhi. Although the battle itself was not of the greatest significance militarily, this was a pivotal moment in history, as it marks the spread of Chinese papermaking[162][163] into regions west of China as captured Chinese soldiers shared the technique of papermaking to the Arabs. These techniques ultimately reached Europe by the 12th century through Arab-controlled Spain.[164] Although they had fought at Talas, on June 11, 758, an Abbasid embassy arrived at Chang'an simultaneously with the Uyghurs bearing gifts for the Tang emperor.[165] In 788–789 the Chinese concluded a military alliance with the Uyghur Turks who twice defeated the Tibetans, in 789 near the town of Gaochang in Dzungaria, and in 791 near Ningxia on the Yellow River.[166]

Joseph Needham writes that a tributary embassy came to the court of Emperor Taizong in 643 from the Patriarch of Antioch.[167] However, Friedrich Hirth and other sinologists such as S. A. M. Adshead have identified fulin (拂菻) in the Old and New Book of Tang as the Byzantine Empire, which those histories directly associated with Daqin (i.e. the Roman Empire).[168][169][170] The embassy sent in 643 by Boduoli (波多力) was identified as Byzantine ruler Constans II Pogonatos, and further embassies were recorded as being sent into the 8th century.[169][170][168] Adshead offers a different transliteration stemming from "patriarch" or "patrician", possibly a reference to one of the acting regents for the young Byzantine monarch.[171] The Old and New Book of Tang also provide a description of the Byzantine capital Constantinople,[172][173] including how it was besieged by the Da Shi (大食, i.e. the Umayyad Caliphate) forces of Mu'awiya I, who forced them to pay tribute to the Arabs.[169][174]

Economy

Through use of the land trade along the Silk Road and maritime trade by sail at sea, the Tang were able to acquire and gain many new technologies, cultural practices, rare luxury, and contemporary items. From Europe, the Middle East, Central and South Asia, the Tang dynasty were able to acquire new ideas in fashion, new types of ceramics, and improved silver-smithing techniques. The Tang also gradually adopted the foreign concept of stools and chairs as seating, whereas the Chinese beforehand always sat on mats placed on the floor.[176] People of the Middle East coveted and purchased Chinese goods in bulk, including silks, porcelain, and lacquerwares.[177] Songs, dances, and musical instruments from foreign regions became popular in China during the Tang dynasty.[178][179] These musical instruments included oboes, flutes, and small lacquered drums from Kucha in the Tarim Basin, and percussion instruments from India such as cymbals.[178] At the court there were nine musical ensembles (expanded from seven in the Sui dynasty) that played ecletic Asian music.[180]

There was great interaction with India, a hub for Buddhist knowledge, with famous travellers such as Xuanzang (d. 664) visiting the South Asian state. After a 17-year trip, Xuanzang managed to bring back valuable Sanskrit texts to be translated into Chinese. There was also a Turkic–Chinese dictionary available for serious scholars and students, while Turkic folk songs gave inspiration to some Chinese poetry.[181][182] In the interior of China, trade was facilitated by the Grand Canal and the Tang government's rationalisation of the greater canal system that reduced costs of transporting grain and other commodities.[52] The state also managed roughly 32,100 km (19,900 mi) of postal service routes by horse or boat.[183]

Silk Road

Although the Silk Road from China to Europe and the Western world was initially formulated during the reign of Emperor Wu (141–87 BC) during the Han, it was reopened by the Tang in 639, when Hou Junji (d. 643) conquered the West, and remained open for almost four decades. It was closed after the Tibetans captured it in 678, but in 699, the Silk Road reopened when the Tang reconquered the Four Garrisons of Anxi originally installed in 640,[184] once again connecting China directly to the West for land-based trade.[185]

The Tang captured the vital route through the Gilgit valley from Tibet in 722, lost it to the Tibetans in 737, and regained it under the command of the Goguryeo-Korean General Gao Xianzhi.[186] When the An Lushan rebellion ended in 763, the Tang Empire withdrew its troops from its western lands, allowing the Tibetan Empire to largely cut off China's direct access to the Silk Road. An internal rebellion in 848 ousted the Tibetan rulers, and the Tang regained the northwestern prefectures from Tibet in 851. These lands contained crucial grazing areas and pastures for raising horses that the Tang dynasty desperately needed.[153][187]

Despite the many expatriate European travellers coming into China to live and trade, many travellers, mainly religious monks and missionaries, recorded China's stringent immigrant laws. As the monk Xuanzang and many other monk travellers attested to, there were many government checkpoints along the Silk Road that examined travel permits into the Tang Empire. Furthermore, banditry was a problem along the checkpoints and oasis towns, as Xuanzang also recorded that his group of travellers were assaulted by bandits on multiple occasions.[177]

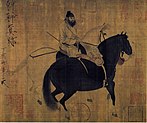

The Silk Road also affected the art from the period. Horses became a significant symbol of prosperity and power as well as an instrument of military and diplomatic policy. Horses were also revered as a relative of the dragon.[188]

-

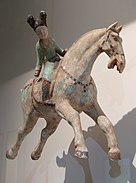

A Tang sancai glazed tomb figure an equestrian figure on a horse

-

A sancai glazed horse tomb figure excavated from Xi'an

Seaports and maritime trade

Chinese envoys had been sailing through the Indian Ocean to states of India as early as the 2nd century BC,[189][190] yet it was during the Tang dynasty that a strong Chinese maritime presence could be found in the Persian Gulf and Red Sea, into Persia, Mesopotamia (sailing up the Euphrates River in modern-day Iraq), Arabia, Egypt, Aksum (Ethiopia), and Somalia in the Horn of Africa.[191]

During the Tang dynasty, thousands of foreign expatriate merchants came and lived in numerous Chinese cities to do business with China, including Persians, Arabs, Hindu Indians, Malays, Bengalis, Sinhalese, Khmers, Chams, Jews and Nestorian Christians of the Near East.[192][193] In 748, the Buddhist monk Jian Zhen described Guangzhou as a bustling mercantile business center where many large and impressive foreign ships came to dock. He wrote that "many large ships came from Borneo, Persia, Qunglun (Java) ... with ... spices, pearls, and jade piled up mountain high",[194][195] as written in the Yue Jue Shu (Lost Records of the State of Yue). Relations with the Arabs were often strained: When the imperial government was attempting to quell the An Lushan rebellion, Arab and Persian pirates burned and looted Canton on October 30, 758. [153] The Tang government reacted by shutting the port of Canton down for roughly five decades; thus, foreign vessels docked at Hanoi instead.[196] However, when the port reopened, it continued to thrive. In 851, the Arab merchant Sulaiman al-Tajir observed the manufacturing of porcelain in Guangzhou and admired its transparent quality.[197] He also provided a description of Guangzhou's landmarks, granaries, local government administration, some of its written records, treatment of travellers, along with the use of ceramics, rice, wine, and tea.[198] Their presence ended in the vengeful Guangzhou massacre by the rebel Huang Chao in 878, who purportedly slaughtered thousands regardless of ethnicity.[81][199][200] Huang's rebellion was eventually suppressed in 884.

Vessels from other East Asian states such as Silla, Bohai and the Hizen Province of Japan were all involved in the Yellow Sea trade, which Silla of Korea dominated. After Silla and Japan reopened renewed hostilities in the late 7th century, most Japanese maritime merchants chose to set sail from Nagasaki towards the mouth of the Huai River, the Yangtze River, and even as far south as the Hangzhou Bay in order to avoid Korean ships in the Yellow Sea.[201][202] In order to sail back to Japan in 838, the Japanese embassy to China procured nine ships and sixty Korean sailors from the Korean wards of Chuzhou and Lianshui cities along the Huai River.[203] It is also known that Chinese trade ships travelling to Japan set sail from the various ports along the coasts of Zhejiang and Fujian provinces.[204]

The Chinese engaged in large-scale production for overseas export by at least the time of the Tang. This was proven by the discovery of the Belitung shipwreck, a silt-preserved shipwrecked Arabian dhow in the Gaspar Strait near Belitung, which had 63,000 pieces of Tang ceramics, silver, and gold (including a Changsha bowl inscribed with a date corresponding to 826, roughly confirmed by radiocarbon dating of star anise at the wreck).[205] Beginning in 785, the Chinese began to call regularly at Sufala on the East African coast in order to cut out Arab middlemen,[206] with various contemporary Chinese sources giving detailed descriptions of trade in Africa. The official and geographer Jia Dan (730–805) wrote of two common sea trade routes in his day: one from the coast of the Bohai Sea towards Korea and another from Guangzhou through Malacca towards the Nicobar Islands, Sri Lanka and India, the eastern and northern shores of the Arabian Sea to the Euphrates River.[207] In 863, the Chinese author Duan Chengshi (d. 863) provided a detailed description of the slave trade, ivory trade, and ambergris trade in a country called Bobali, which historians suggest was Berbera in Somalia.[208] In Fustat, Egypt, the fame of Chinese ceramics there led to an enormous demand for Chinese goods; hence Chinese often travelled there.[209][210] From this time period, the Arab merchant Shulama once wrote of his admiration for Chinese seafaring junks, but noted that their draft was too deep for them to enter the Euphrates River, which forced them to ferry passengers and cargo in small boats. Shulama also noted that Chinese ships were often very large, with capacities up to 700 passengers.[207][211]

Culture and society

Both the Sui and Tang dynasties had turned away from the more feudal culture of the preceding Northern Dynasties, in favour of staunch civil Confucianism.[9] The governmental system was supported by a large class of Confucian intellectuals selected through either civil service examinations or recommendations. In the Tang period, Taoism and Buddhism were commonly practised ideologies that played a large role in people's daily lives. The Tang Chinese enjoyed feasting, drinking, holidays, sports, and all sorts of entertainment, while Chinese literature blossomed and was more widely accessible with new printing methods. Rich commoners and nobles who worshipped spirits wanted them to know "how important and how admirable they were", so they "wrote or commissioned their own obituaries" and buried figures along with their bodies to ward off evil spirits.[212]

Chang'an

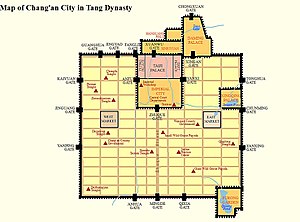

Although Chang'an had serves as the capital during the earlier Han and Jin dynasties, after subsequent destruction in warfare, it was the Sui dynasty model that comprised the Tang-era capital. The roughly square dimensions of the city had 10 km (6.2 mi) of outer walls running east to west, and more than 8 km (5.0 mi) of outer walls running north to south.[31] The royal palace, the Taiji Palace, stood north of the city's central axis.[213] From the large Mingde Gates mid-center on the main southern wall, a wide city avenue stretched all the way north to the central administrative city, behind which was the Chentian Gate of the royal palace, or Imperial City. Intersecting this were fourteen main streets running east to west, while eleven main streets ran north to south. These main intersecting roads formed 108 rectangular wards with walls and four gates each, each filled with multiple city blocks. The city was made famous for this checkerboard pattern of main roads with walled and gated districts, its layout even mentioned in one of Du Fu's poems.[214] During the Heian period, cities like Heian-kyō (present-day Kyoto) were arranged in the checkerboard street in accordance with traditional geomancy, following the Chang'an model. Of Chang'an's 108 wards, two were designated as government-supervised markets, and other space reserved for temples, gardens, ponds, etc.[215] Throughout the entire city, there were 111 Buddhist monasteries, 41 Taoist abbeys, 38 family shrines, 2 official temples, 7 churches of foreign religions, 10 city wards with provincial transmission offices, 12 major inns, and 6 graveyards. Some city wards were literally filled with open public playing fields or the backyards of lavish mansions for playing horse polo and cuju (Chinese soccer).[216] In 662, Emperor Gaozong moved the imperial court to the Daming Palace, which became the political center of the empire and served as the royal residence of the Tang emperors for more than 220 years.[217]

The Tang capital was the largest city in the world at its time, with the population of its wards and suburban countryside reaching two million inhabitants.[31] The Tang capital was very cosmopolitan, with ethnicities of Persia, Central Asia, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Tibet, India, and many other places living within. Naturally, with this plethora of different ethnicities living in Chang'an, there were also many different practised religions, such as Buddhism, Nestorian Christianity, and Zoroastrianism, among others.[218] With the open access to China that the Silk Road to the west facilitated, many foreign settlers were able to move east to China, while the city of Chang'an itself had about 25,000 foreigners living within.[177] Exotic green-eyed, blond-haired Tocharian ladies serving wine in agate and amber cups, singing, and dancing at taverns attracted customers. If a foreigner in China pursued a Chinese woman for marriage, he was required to stay in China and was unable to take his bride back to his homeland, as stated in a law passed in 628 to protect women from temporary marriages with foreign envoys. Several laws enforcing segregation of foreigners from Chinese were passed during the Tang. In 779, the Tang issued an edict which forced Uyghurs in the capital, Chang'an, to wear their ethnic dress, stopped them from marrying Chinese females, and banned them from passing off as Chinese.[219]

Chang'an was the center of the central government, the home of the imperial family, and was filled with splendor and wealth. However, incidentally it was not the economic hub during the Tang dynasty. The city of Yangzhou along the Grand Canal and close to the Yangtze was the greatest economic center during the Tang.[192][220]

Yangzhou was the headquarters for the Tang government's salt monopoly, and was the greatest industrial center of China. It acted as a midpoint in shipping of foreign goods to be distributed to the major cities of the north.[192] Much like the seaport of Guangzhou in the south, Yangzhou had thousands of foreign traders from across Asia.[220][221]

There was also the secondary capital city of Luoyang, which was the favoured capital of the two by Empress Wu. In 691, she had more than 100,000 families from the region around Chang'an move to Luoyang. With a population of about a million, Luoyang became the second largest city in the empire, and with its closeness to the Luo River it benefited from southern agricultural fertility and trade traffic of the Grand Canal. However, the Tang court eventually demoted its capital status and did not visit Luoyang after 743, when Chang'an's problem of acquiring adequate supplies and stores for the year was solved.[192] As early as 736, granaries were built at critical points along the route from Yangzhou to Chang'an, which eliminated shipment delays, spoilage, and pilfering. An artificial lake used as a transshipment pool was dredged east of Chang'an in 743, where curious northerners could finally see the array of boats found in southern China, delivering tax and tribute items to the imperial court.[222]

Literature

The Tang dynasty was a golden age of Chinese literature and art. Over 48,900 poems penned during the Tang, representing over 2,200 authors, have survived to the present day.[223][224] Skill in the composition of poetry became a required study for those wishing to pass imperial examinations,[225] while poetry was also heavily competitive; poetry contests among guests at banquets and courtiers were common.[226] Poetry styles that were popular in the Tang included gushi and jintishi, with the renowned poet Li Bai (701–762) famous for the former style, and poets like Wang Wei (701–761) and Cui Hao (704–754) famous for their use of the latter. Jintishi poetry, or regulated verse, is in the form of eight-line stanzas or seven characters per line with a fixed pattern of tones that required the second and third couplets to be antithetical (although the antithesis is often lost in translation to other languages).[227] Tang poems remained popular and great emulation of Tang era poetry began in the Song dynasty; in that period, Yan Yu (嚴羽; fl. 1194–1245) was the first to confer the poetry of the High Tang (c. 713 – 766) with "canonical status within the classical poetic tradition". Yan Yu reserved the position of highest esteem among all Tang poets for Du Fu (712–770), who was not viewed as such in his own era, and was branded by his peers as an anti-traditional rebel.[228]

The Classical Prose Movement was spurred in large part by the writings of Tang authors Liu Zongyuan (773–819) and Han Yu (768–824). This new prose style broke away from the poetry tradition of piantiwen (駢體文; 'parallel prose') style begun in the Han dynasty. Although writers of the Classical Prose Movement imitated piantiwen, they criticised it for its often vague content and lack of colloquial language, focusing more on clarity and precision to make their writing more direct.[229] This guwen (archaic prose) style can be traced back to Han Yu, and would become largely associated with orthodox Neo-Confucianism.[230]

Short story fiction and tales were also popular during the Tang, one of the more famous ones being Yingying's Biography by Yuan Zhen (779–831), which was widely circulated in his own time and by the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) became the basis for Chinese opera.[231][232] Timothy C. Wong places this story within the wider context of Tang love tales, which often share the plot designs of quick passion, inescapable societal pressure leading to the abandonment of romance, followed by a period of melancholy.[233] Wong states that this scheme lacks the undying vows and total self-commitment to love found in Western romances such as Romeo and Juliet, but that underlying traditional Chinese values of indivisibility of self from one's environment, including from society) served to create the necessary fictional device of romantic tension.[234]

Large encyclopaedias were published during the Tang: the Yiwen Leiju was compiled in 624 under chief editor Ouyang Xun (557–641), Linghu Defen (582–666) and Chen Shuda (d. 635). By 729, the team led by scholar Gautama Siddha (fl. 8th century), an ethnic Indian born in Chang'an, had finished compiling the Treatise on Astrology of the Kaiyuan Era, an astrological encyclopaedia.

Chinese geographers, such as Jia Dan, wrote accurate descriptions of places far beyond Tang territory. In his work written between 785 and 805, Jia described the sea route going into the mouth of the Persian Gulf, and that the medieval Iranians had erected 'ornamental pillars' in the sea that acted as lighthouse beacons for ships that might go astray.[235] Arabic authors writing a century after Jia, such as al-Masudi and al-Maqdisi, also mentioned these structures in their accounts, confirming Jia's reports. The Tang diplomat Wang Xuance travelled to Magadha, in present-day northeast India, during the 7th century.[236] Afterwards, he wrote the Zhang Tianzhu Guotu (Illustrated Accounts of Central India), a book which contained a large body of geographical information.[237]

Many histories of previous dynasties were compiled between 636 and 659 by court officials during and shortly after the reign of Emperor Taizong of Tang. These included the Book of Liang, Book of Chen, Book of Northern Qi, Book of Zhou, Book of Sui, Book of Jin, History of Northern Dynasties and the History of Southern Dynasties. Although not included in the official Twenty-Four Histories, the Tongdian and Tang Huiyao were nonetheless valuable written historical works of the Tang period. The Shitong written by Liu Zhiji in 710, was a meta-history that surveyed the tradition of Chinese historiography to date. The Great Tang Records on the Western Regions, compiled by Bianji, recounted the journey of Xuanzang, the Tang era's most renowned Buddhist monk.

Other important literature included Duan Chengshi's (d. 863) Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang, an entertaining collection of foreign legends and hearsay, reports on natural phenomena, short anecdotes, mythical and mundane tales, as well as notes on various subjects. The exact literary category or classification that Duan's large informal narrative would fit into is still debated among scholars and historians.[238]

Religion and philosophy

Since ancient times, some Chinese had believed in folk religion and Taoism that incorporated many deities. Practitioners believed the Tao and the afterlife was a reality parallel to the living world, complete with its own bureaucracy and afterlife currency needed by dead ancestors. Funerary practices included providing the deceased with everything they might need in the afterlife, including animals, servants, entertainers, hunters, homes, and officials. This ideal is reflected in Tang art.[239] This is also reflected in many short stories written in the Tang about people accidentally winding up in the realm of the dead, only to come back and report their experiences.[240]

Buddhism, originating in India around the time of Confucius, continued its influence during the Tang period and was accepted by some members of imperial family, becoming thoroughly sinicised and a permanent part of Chinese traditional culture. In an age before Neo-Confucianism and figures such as Zhu Xi (1130–1200), Buddhism had begun to flourish in China during the Northern and Southern dynasties, and became the dominant ideology during the prosperous Tang. Buddhist monasteries played an integral role in Chinese society, offering lodging for travellers in remote areas, schools for children throughout the country, and a place for urban literati to stage social events and gatherings such as going-away parties. Buddhist monasteries were also engaged in the economy, since their land property and serfs gave them enough revenues to set up mills, oil presses, and other enterprises.[241][242] Although the monasteries retained 'serfs', these monastery dependents could actually own property and employ others to help them in their work, including their own slaves.[243]

The prominent status of Buddhism in Chinese culture began to decline as the dynasty and central government declined as well during the late 8th century to 9th century. Buddhist convents and temples that were exempt from state taxes beforehand were targeted by the state for taxation. In 845, Emperor Wuzong finally shut down 4,600 Buddhist monasteries along with 40,000 temples and shrines, forcing 260,000 Buddhist monks and nuns to return to secular] life;[244][245] this episode would later be dubbed one of the Four Buddhist Persecutions in China. Although the ban was lifted just a few years after, Buddhism never regained its once dominant status in Chinese culture.[244][245][246][247] This situation also came about through a revival of interest in native Chinese philosophies such as Confucianism and Taoism. Han Yu (786–824)—who Arthur F. Wright stated was a "brilliant polemicist and ardent xenophobe"—was one of the first men of the Tang to denounce Buddhism.[248] Although his contemporaries found him crude and obnoxious, he foreshadowed the later persecution of Buddhism in the Tang, as well as the revival of Confucian theory with the rise of Neo-Confucianism of the Song dynasty.[248] Nonetheless, Chán Buddhism gained popularity among the educated elite.[244] There were also many famous Chan monks from the Tang era, such as Mazu Daoyi, Baizhang, and Huangbo Xiyun. The sect of Pure Land Buddhism initiated by the Chinese monk Huiyuan (334–416) was also just as popular as Chan Buddhism during the Tang.[249]

Rivaling Buddhism was Taoism, a native Chinese philosophical and religious belief system that found its roots in the Tao Te Ching and the Zhuangzi. The ruling Li family of the Tang dynasty actually claimed descent from Laozi, traditionally credited as the author of the Tao Te Ching.[251] On numerous occasions where Tang princes would become crown prince or Tang princesses taking vows as Taoist priestesses, their lavish former mansions would be converted into Taoist abbeys and places of worship.[251] Many Taoists were associated with alchemy in their pursuits to find an elixir of immortality and a means to create gold from concocted mixtures of many other elements. Although they never achieved their goals in either of these futile pursuits, they did contribute to the discovery of new metal alloys, porcelain products, and new dyes. The historian Joseph Needham labelled the work of the Taoist alchemists as "protoscience rather than pseudoscience".[252] However, the close connection between Taoism and alchemy, which some sinologists have asserted, is refuted by Nathan Sivin, who states that alchemy was just as prominent (if not more so) in the secular sphere and practised more often by laymen.[253]

The Tang dynasty also officially recognised various foreign religions. The Assyrian Church of the East, otherwise known as the Nestorian Church or the Church of the East in China, was given recognition by the Tang court. In 781, the Nestorian Stele was created in order to honour the achievements of their community in China. A Christian monastery was established in Shaanxi province where the Daqin Pagoda still stands, and inside the pagoda there is Christian-themed artwork. Although the religion largely died out after the Tang, it was revived in China following the Mongol invasions of the 13th century.[254]

Although the Sogdians had been responsible for transmitting Buddhism to China from India during the 2nd–4th centuries, soon afterwards they largely converted to Zoroastrianism due to their links to Sasanian Persia. Sogdian merchants and their families living in cities such as Chang'an, Luoyang, and Xiangyang usually built a Zoroastrian temple once their local communities grew larger than 100 households.[255] Sogdians were also responsible for spreading Manicheism in China and the Uyghur Khaganate. The Uyghurs built the first Manichean monastery in China in 768; in 843, the Tang government ordered that the property of all Manichean monasteries be confiscated in response to the outbreak of war with the Uyghurs. With the blanket ban on foreign religions two years later, Manicheism was driven underground and never flourished in China again.[256]

Leisure

More than earlier periods, the Tang era was renowned for the time reserved for leisure activities, especially among the upper classes. Many outdoor sports and activities were enjoyed during the Tang, including archery,[257] hunting,[258] horse polo,[259] cuju (soccer), cockfighting,[260] and even tug of war.[261] Government officials were granted vacations during their tenure in office. Officials were granted 30 days off every three years to visit their parents if they lived 1,000 mi (1,600 km) away, or 15 days off if the parents lived more than 167 mi (269 km) away (travel time not included). Officials were granted nine days of vacation time for weddings of a son or daughter, and either five, three, or one days/day off for the nuptials of close relatives (travel time not included). Officials also received a total of three days off for their son's capping initiation rite into manhood, and one day off for the ceremony of initiation rite of a close relative's son.[262]

Traditional Chinese holidays such as Chinese New Year, Lantern Festival, Cold Food Festival, and others were universal holidays. In Chang'an, there was always lively celebration, especially for the Lantern Festival since the city's nighttime curfew was lifted by the government for three days straight. Between 628 and 758, the imperial throne bestowed a total of sixty-nine grand carnivals nationwide, granted by the emperor in the case of special circumstances such as important military victories, abundant harvests after a long drought or famine, the granting of amnesties, or the instalment of a new crown prince.[263] For special celebration in the Tang era, lavish and gargantuan-sized feasts were sometimes prepared, as the imperial court had staffed agencies to prepare the meals. This included a prepared feast for 1,100 elders of Chang'an in 664, a feast held for 3,500 officers of the Divine Strategy Army in 768, and one in 826 for 1,200 members of the imperial family and women of the palace.[264] Alcohol consumption was a prominent facet of Chinese culture; people during the Tang drank for nearly every social event. An 8th-century court official allegedly had a serpent-shaped structure called the 'ale grotto' built on the ground floor using a total of 50,000 bricks, which featured bowls from which each of his friends could drink.[265]

Status in clothing

In general, garments were made from silk, wool, or linen depending on your social status and what you could afford. Furthermore, there were laws that specified what kinds of clothing could be worn by whom. The color of the clothing also indicated rank. During this period, China's power, culture, economy, and influence were thriving. As a result, women could afford to wear loose-fitting, wide-sleeved garments. Even lower-class women's robes had sleeves four to five feet wide.[266][better source needed]

Position of women

Concepts of women's social rights and social status during the Tang era were notably liberal-minded for the period. However, this was largely reserved for urban women of elite status, as men and women in the rural countryside laboured hard in their different set of tasks; with wives and daughters responsible for more domestic tasks of weaving textiles and rearing of silk worms, while men tended to farming in the fields.[112] There were many women in the Tang era who gained access to religious authority by taking vows as Taoist priestesses.[251]

In Chang'an, ordinary courtesans inhabited the North Hamlet.[267] They were generally knowledgeable in the rules of drinking games, and received particular training in table manners.[268] While renowned for their politeness, courtesans were reputed to dominate conversations among elite men, and as being unafraid to openly criticise the rudeness of prominent male guests, including for talking too much, too loudly, or for boasting of their accomplishments.[269] Courtesans were sometimes beaten by their procuring madames.[270]

Gējìs, or professional singing courtesans, were culturally prominent, and joined talent agencies called jiaofang. The emperor selected particularly talented women from the outer jiaofang to form the spring court, who were supplemented by courtesans from other troupes.[271] During the Tang, singing courtesans who were also talented in the poetry.[272] In addition to singing, some courtesans composed their own songs, and even popularised a new form of lyrical verse that incorporated quotations of famous historical figures.[223]