Tarjei Vesaas

Tarjei Vesaas | |

|---|---|

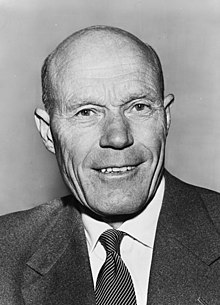

Tarjei Vesaas (1967) | |

| Born | August 20, 1897 Vinje, Telemark, Norway |

| Died | March 15, 1970 (aged 72) Oslo, Norway |

| Language | Nynorsk |

| Nationality | Norwegian |

| Notable awards | Gyldendals legat (1943) Doblougprisen (1957) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Olav Vesaas Guri Vesaas |

| Relatives | Sven Moren (father-in-law) Sigmund Moren (brother-in-law) |

Tarjei Vesaas (20 August 1897 – 15 March 1970) was a Norwegian poet and novelist. Vesaas is widely considered to be one of Norway's greatest writers of the twentieth century and perhaps its most important since World War II.[1]

Biography[edit]

Vesaas was born in Vinje, Telemark, Norway to Olav Vesaas (1870–1951), a farmer and Signe Øygarden (1870–1953), a teacher.[2] He was the oldest of three sons, and was guilt-ridden by his refusal to take over the family farm which had been in the family for almost 300 years.[3] He was forced to leave school at fourteen, and never had any higher education except for a year at Voss Folk High School from 1917–18.[4][3][5] Lars Eskeland, Vesaas' teacher at Voss Folk, translated some of Rabindranath Tagore's writings; these later influenced Vesaas' writing style.[6]

He spent much of his youth in solitude, seeking comfort and solace in nature. He married the writer Halldis Moren Vesaas (the daughter of Sven Moren and the sister of Sigmund Moren) and moved to Midtbø in his home district of Vinje in 1934. They had two children: a son, Olav Vesaas and a daughter, Guri Vesaas.[2][7]

Career[edit]

Vesaas' work is characterized by simple, terse, and symbolic prose.[3] His stories often feature rural people who go through severe psychological changes. These works also are characterized by their usage of the demanding Norwegian landscape and themes such as guilt and death.[8][3] His mastery of the nynorsk language has contributed to its acceptance as a medium of world class literature.[2]

Early writing (1923–1933)[edit]

Vesaas' early writing focused on the neo-romantic tradition, with prominent religious sentiments.[2][6] These early works had many authorial influences, including Rabindranath Tagore; Rudyard Kipling; Selma Lagerlöf, especially her Gösta Berling's Saga; Knut Hamsun, particularly his neo-romantic novels, Pan and Victoria; and Henrik Ibsen.[6][4] The poems of Edith Södergran caused him to shift more towards the free verse form.[9]

Vesaas sold his first short stories to a magazine in the early 1920s.[3] His debut was in 1923 with Menneskebonn (Children of Man). The novel tells the story of a boy who loses his parents and lover, yet still believes in the importance of being good.[4] A year later, his second novel Huskuld the Herald was published, which tells the story of a village eccentric whose final years are brightened when he befriends a young child abandoned by his mother.[4]

Vesaas' first successful novel came with the release of Dei svarte hestane (The Black Horses) in 1928.[2][4] It also marked the increase in realism and contemporary awareness in Vesaas' novels.[2] The next year, Vesaas published his first short story collection, Klokka i haugen (The Bell in the Mound), which contained seven stories written expressly for the collection. It was the first of his books to be translated into another language.[10]

In 1930, Vesaas published Fars reise (Father's Journey), the first in a tetralogy focusing on protagonist Klas Dyregodt. The second and third books in the series, Sigrid Stallbrokk and Dei ukjende mennene (The Unknown Men), were published in 1931 and 1932, respectively.[2] Although it was originally intended as a trilogy,[11] the final novel in the series, Hjarta høyrer sine heimlandstonar (The Heart Hears Its Native Music), was published six years later in 1938. It has a much lighter tone than the first three novels.[2][4]

In 1933, Vesaas' novel Sandeltreet (The Sandalwood) was published. The book was written over the course of a few weeks in the summer of 1933 after Vesaas' last trip abroad. It focuses on a pregnant woman who believes she will not survive the delivery process, so she goes on a journey to experience as much of life as possible.[9]

Literary breakthrough and success (1934–1939)[edit]

Vesaas' breakthrough was in 1934 with The Great Cycle (Det store spelet), which was praised by contemporary critics. The sequel, Kvinnor ropar heim (Women Call Home), was published a year later, in 1935.[2]

Also in 1934, Vesaas' second play Ultimatum was published; it was primarily written two years earlier in September 1932 in Strasbourg.[12] Ultimatum focuses on the reactions of a group of young people just before a war breaks out. It features a flashing neon sign, adapted from the stage effects Vesaas had seen while traveling in Germany. The play was inspired by Vesaas' frightened reaction to German soldiers marching and holding swastikas.[9] It was not well received by Norwegian audiences when it was first performed at Det Norske Teatret in Oslo.[9]

Two years later saw the publication of Vesaas' second short story collection, Leiret og hjulet (The Clay and the Wheel).[4]

Experimentation (1940–1956)[edit]

In the winter and spring of 1945, Vesaas wrote Huset i mørkret (The House in the Dark), an allegorical novel about the German occupation of Norway and the Norwegian resistance movement during the Second World War.[13][14] Due to the dangers of owning the manuscript, it was hidden away in a zinc box until the end of the occupation in May 1945. The book was published in the autumn later that year.[2][14]

Vesaas' novel Bleikeplassen (The Bleaching Place), published in 1946, is an extensively reworked version of his unpublished play Vaskehuset, which he had withdrawn from its public premiere six years earlier.[9] In 1948, his novel Tårnet (The Tower) was published.[4] Both Bleikeplassen and Tårnet were written before Huset i mørkret but published later because of the German occupation.[2]

The Birds and The Ice Palace (1957–1963)[edit]

The most famous of his works are The Ice Palace (Is-slottet), a story of two girls who build a profoundly strong relationship, and The Birds (Fuglane), a story of an adult of a simple childish mind, which through his tenderhearted empathy and imagination bears the role of a seer or writer. He was awarded the Nordic Council's Literature Prize in 1963 for The Ice Palace.

Later works (1964–1970)[edit]

A prolific author, he won a number of awards, including the Gyldendal's Endowment in 1943, Dobloug Prize in 1957, and the Venice Prize in 1953 for The Winds. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature on 57 occasions (once in 1946, and often multiple times every year between 1950 and 1970).[15]

His novels have been translated into 28 languages. Several of his books have been translated into English—many of them published by Peter Owen Publishers—among them Spring Night, The Birds, Through Naked Branches, and The Ice Palace.[8]

Awards[edit]

- 1943 – Gyldendal's Endowment (Gyldendals legat)

- 1946 – Melsom Prize (Melsom-prisen)

- 1957 – Dobloug Prize (Doblougprisen)

- 1964 – Nordic Council's Literature Prize (Nordisk råds litteraturpris)

- 1967 – Norwegian Booksellers' Prize (Bokhandlerprisen)

Works[edit]

Novels[edit]

- Menneskebonn (Children of Man, 1923)

- Sendemann Huskuld (Huskuld the Herald, 1924)

- Dei svarte hestane (The Black Horses, 1928)

- Sandeltreet (The Sandalwood, 1933)

- Kimen (The Seed, 1940)

- Translated by Kenneth G. Chapman (Peter Owen Publishers, 1964)

- Huset i mørkret (The House in the Dark, 1945)

- Translated by Elizabeth Rokkan (Peter Owen Publishers, 1976)

- Bleikeplassen (The Bleaching Place, 1946)

- Translated by Elizabeth Rokkan (Peter Owen Publishers, 1981); published as The Bleaching Yard

- Tårnet (The Tower, 1948)

- Signalet (The Signal, 1950)

- Vårnatt (Spring Night, 1954)

- Translated by Kenneth G. Chapman (Peter Owen Publishers, 1972)

- Fuglane (The Birds, 1957)

- Translated by Torbjørn Støverud and Michael Barnes (Peter Owen Publishers, 1968)

- Brannen (The Fire, 1961)

- Is-slottet (The Ice Palace, 1963)

- Translated by Elizabeth Rokkan (Peter Owen Publishers, 1993)

- Bruene (The Bridges, 1966)

- Translated by Elizabeth Rokkan (Peter Owen Publishers, 1969)

- Båten om Kvelden (The Boat in the Evening, 1968)

- Translated by Elizabeth Rokkan (Peter Owen Publishers, 1971)

Grinde Farm series[edit]

- Grindegard: Morgonen (Grinde Farm, 1925)

- Grinde‐kveld, eller Den gode engelen (Evening at Grinde, 1926)

Klas Dyregodt series[edit]

- Fars reise (Father's Journey, 1930)

- Sigrid Stallbrokk (1931)

- Dei ukjende mennene (The Unknown Men, 1932)

- Hjarta høyrer sine heimlandstonar (The Heart Hears Its Native Music, 1938)

The Great Cycle series[edit]

- Det store spelet (The Great Cycle, 1934)

- Translated by Elizabeth Rokkan (University of Wisconsin Press, 1967)

- Kvinnor ropar heim (Women Call Home, 1935)

Poetry[edit]

- Kjeldene (The Springs, 1946)

- Leiken og lynet (The Game and the Lightning, 1947)

- Lykka for ferdesmenn (Wanderers’ Happiness, 1949)

- Løynde eldars land (Land of Hidden Fires, 1953)

- Translated by Fritz König and Jerry Crisp (Wayne State University Press, 1973)

- Ver ny, vår draum (May Our Dream Stay New, 1956)

- Liv ved straumen (Life by the Stream, 1970)

Short story collections[edit]

- Klokka i haugen (The Bell in the Mound, 1929)

- Leiret og hjulet (The Clay and the Wheel, 1936)

- Vindane (The Winds, 1952)

- Ein vakker dag (A Lovely Day, 1959)

Plays[edit]

- Guds bustader (God’s Abodes, 1925)

- Ultimatum (1934)

- Morgonvinden (Morning Wind, 1947)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Nomination Database". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2017-01-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gimnes, Steinar (February 25, 2020), "Tarjei Vesaas", Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian Bokmål), retrieved October 21, 2020

- ^ a b c d e "TARJEI VESAAS, 72, NORWEGIAN POET". The New York Times. March 16, 1970. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Næss, Harald S. (1967). Introduction. Det store spelet [The Great Cycle]. By Vesaas, Tarjei (in Norwegian Nynorsk). Translated by Rokkan, Elizabeth. University of Wisconsin-Madison. pp. vii.

- ^ Chapman, Kenneth G. (1970). Tarjei Vesaas. New York: Twayne Publishers. LCCN 78-110715.

- ^ a b c Chapman, Kenneth (May 1969). "Basic Themes and Motives in Vesaas' Earliest Writing". Scandinavian Studies. 41 (2): 126–137 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Halldis Moren Vesaas". Aschehoug. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ a b "Tarjei Vesaas (1897–1970)". Gyldendal Agency. Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Hermundsgård, Frode (2001). "Tarjei Vesaas and German Expressionist Theater". Scandinavian Studies. 73 (2): 125–146 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Chapman 1970, p. 41

- ^ Chapman 1970, p. 42

- ^ Chapman 1970, p. 50

- ^ Chapman 1970, p. 86

- ^ a b Rokkan, Elizabeth (1976). Introduction. Huset i mørkret [The House in the Dark]. By Vesaas, Tarjei (in Norwegian Nynorsk). Translated by Rokkan, Elizabeth. Peter Owen Publishers. ISBN 9780720602937.

- ^ "Tarjei Vesaas - Nomination Database". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

Related reading[edit]

- Encyclopedia of World Literature in the 20th Century, vol. 4, ed. S. R. Serafin, 1999;

- Columbia Dictionary of Modern European Literature, ed. Jean-Albert Bédé & William B. Edgerton, 1980;