Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum

The Coliseum L.A. Coliseum The Grand Old Lady | |

Logo since 2022, first revealed as the stadium's 100th anniversary (2023). | |

The stadium during a football game in 2019 | |

Location in L.A. metro area | |

| Address | 3911 South Figueroa Street |

|---|---|

| Location | Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 34°0′51″N 118°17′16″W / 34.01417°N 118.28778°W |

| Public transit | Expo/Vermont |

| Owner | State of California, Los Angeles County, and City of Los Angeles |

| Operator | University of Southern California |

| Executive suites | 42 |

| Capacity | 77,500 93,607 (pre-2018) [1][2] |

| Surface | Bermuda grass |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | December 21, 1921 |

| Opened | May 1, 1923 |

| Renovated | 1930, 1964, 1977–78, 1983, 1993, 1995, 2011, 2017–2019 |

| Construction cost | US$954,872.98 (original)[3]($17.1 million in 2023 dollars[4]) $954,869 (renovations in 2010) ($1.33 million in 2023 dollars[4]) $315 million (renovations in 2018)[5][6][7] |

| Architect | John and Donald Parkinson (original) DLR Group (renovations) |

| General contractor | Edwards, Widley & Dixon Company (original)[3] Hunt & Hathaway Dinwiddie Construction Company (renovations) |

| Tenants | |

Former List

| |

| Website | |

| lacoliseum.com | |

Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum | |

California Historical Landmark No. 960 | |

The Peristyle plaza entrance to the Coliseum, including the two bronze Olympic statues | |

| Area | 29.2 acres (11.8 ha) |

| Architectural style | Art Moderne[10] |

| NRHP reference No. | 84003866[9] |

| CHISL No. | 960 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 27, 1984 |

| Designated NHL | July 27, 1984[11] |

The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum (also known as the Los Angeles Coliseum or L.A. Coliseum) is a multi-purpose stadium in the Exposition Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, United States. Conceived as a hallmark of civic pride, the Coliseum was commissioned in 1921 as a memorial to Los Angeles veterans of World War I. Completed in 1923, it will become the first stadium to have hosted the Summer Olympics three times when it hosts the 2028 Summer Olympics,[12] previously hosting in 1932 and 1984. It was designated a National Historic Landmark on July 27, 1984, a day before the opening ceremony of the 1984 Summer Olympics.[11]

The stadium serves as the home of the University of Southern California Trojans football team of the Big Ten Conference, and is located directly adjacent to the school's main University Park campus.

The Coliseum is jointly owned by the State of California's Sixth District Agricultural Association, Los Angeles County, and the city of Los Angeles. It is managed and operated by the Auxiliary Services Department of the University of Southern California (USC).[13]

USC granted naming rights to United Airlines in January 2018. After concerns were raised by the Coliseum Commission, which has public oversight of USC's management and operation of the Coliseum, the airline agreed to become the title sponsor of the playing field, naming it United Airlines Field at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.[14]

The Coliseum was the home of the Los Angeles Rams of the National Football League (NFL) from 1946 to 1979, when they moved to Anaheim Stadium in Anaheim, and again from 2016 to 2019, prior to the team's move to SoFi Stadium in Inglewood. The facility had a permanent seating capacity of 93,607 for USC football and Rams games, making it the largest football stadium in the Pac-12 Conference and the NFL.[15] The stadium also was the temporary home of the Los Angeles Dodgers of Major League Baseball (MLB) from 1958 to 1961, and was the host venue for games three, four, and five of the 1959 World Series. It was the site of the first AFL–NFL World Championship Game (later called Super Bowl I) and Super Bowl VII. Additionally, it has served as a home field for a number of other teams, including the 1960 inaugural season for the Los Angeles Chargers, the Los Angeles Raiders of the NFL from 1982 to 1994, and UCLA Bruins football.

From 1959 to 2016, the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena was located adjacent to the Coliseum before it closed in March 2016. BMO Stadium, formerly Banc of California Stadium, a soccer-specific stadium and the home of Major League Soccer (MLS)'s Los Angeles FC, was constructed on the former Sports Arena site, and opened in 2018.

In 2019, USC completed a two year long major renovation of the stadium that included replacing the seating along with the addition of luxury boxes and club suites.[16][17] The $315 million project, funded solely by the university and managed by architectural firm DLR Group, was the first major upgrade of the stadium in twenty years.[18] The improvements and added amenities resulted in a reduced stadium capacity from 92,348 to 77,500.[19]

Operation

[edit]The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission, which consists of six voting members appointed by the three ownership interests and meets on a monthly basis, provides public oversight of the master lease agreement with USC.[20] Under the lease, the university has year-round day-to-day management and operation responsibility for both the Coliseum and BMO Stadium properties.[21] USC's Vice President of Auxiliary Services is the Chief Operating Officer of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, and Coliseum employees are employees of the university.[13][22]

Until 2013, USC had a series of mostly one and two year agreements with the Coliseum Commission – which up to that time had been directly operating the stadium. Those agreements were limited to the university only renting the stadium for USC home football games.[23] On July 29, 2013, after the previously governing Coliseum Commission failed to deliver promised renovations, the Coliseum Commission and USC implemented a significantly more extensive master lease agreement that transferred to USC the responsibility for the long-term management and operation of both the Coliseum and the adjacent BMO Stadium property and the capital renewal of the Coliseum.[24] The 98-year agreement required the university to make approximately $100 million in initial physical repairs to the Coliseum. Additionally, it requires USC pay $1.3 million each year in rent to the State of California for the state-owned land the property occupies in Exposition Park; maintain the Coliseum's physical condition at the same standard used on the USC Campus; and assume all financial obligations for the operations and maintenance of the Coliseum and BMO Stadium Complex.[25][26][27]

USC

[edit]The Coliseum is primarily the home of the USC Trojans football team. Most of USC's regular home games, especially the alternating games with rivals UCLA and Notre Dame, attract a capacity crowd. The current official capacity of the Coliseum is 77,500, with 42 suites, 1,100 club seats, 24 loge boxes, and a 500-person rooftop terrace.[28][29] USC's women lacrosse and soccer teams use the Coliseum for selected games, usually involving major opponents and televised games.[30] USC also rents the Coliseum to various events, including international soccer games, musical concerts and other large outdoor events.[31]

In May 2021, due to the previous year of local COVID-19 restrictions, USC held commencement ceremonies in the Coliseum for graduating students from the classes of 2020 and 2021. Ceremonies were held in the Coliseum twice a day for a week, with over 36,000 diplomas (including undergraduate and graduate degrees and certificates) were awarded. It was the first time in 70 years that USC had held its commencement in the stadium.[32] In September 2024 the university announced that its main commencement ceremony was regularly attracting more than 60,000 guests and had outgrown all venues on campus, and beginning with the May 2025 ceremony it would be moving to the Coliseum.[33]

History

[edit]Planning

[edit]

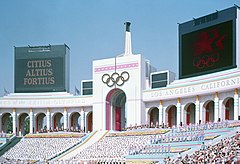

The Coliseum was commissioned in 1921 as a memorial to L.A. veterans of World War I (rededicated to all United States veterans of the war in 1968).[34] The groundbreaking ceremony took place on December 21, 1921, with construction being completed in just over 16 months, on May 1, 1923.[35] Designed by John and Donald Parkinson, the original bowl's initial construction costs were $954,873. When the Coliseum opened in 1923, it was the largest stadium in Los Angeles, with a capacity of 75,144. In 1930, however, with the Olympics due in two years, the stadium was extended upward to seventy-nine rows of seats with two tiers of tunnels, expanding the seating capacity to 101,574. The physical structure of a bowl-shaped configuration for the Coliseum was undoubtedly inspired by the earlier Yale Bowl which was built in 1914. The now-signature Olympic torch was added, and the stadium was briefly known as Olympic Stadium. The Olympic cauldron torch which burned through both Games remains above the peristyle at the east end of the stadium as a reminder of this, as do the Olympic rings symbols over one of the main entrances. Originally for the 1984 games, burnable Olympic Rings and a 25-step hydraulic staircase were added inside in the front of the coliseum to allow the cauldron to be lit by lifting up the stairs to the burnable Olympic Rings, which brought the flame to the cauldron on top.[36] The football field runs east to west with the press box on the south side of the stadium.

The current jumbotrons to each side of the peristyle were installed in 2017, and replaced a scoreboard and video screen that towered over the peristyle dating back to 1983; they replaced a smaller scoreboard above the center arch installed in 1972, which in turn supplanted the 1937 model, one of the first all-electric scoreboards in the nation. Over the years new light towers have been placed along the north and south rims. The large analog clock and thermometer over the office windows at either end of the peristyle were installed in 1955. In the mid- and late 1950s, the press box was renovated, and the "Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum" lettering and Olympic rings, lighted at night, were added to the eastern face of the peristyle tower. Between the double peristyle arches at the east end is the Coliseum's "Court of Honor" plaques, recognizing many of the memorable events and participants in its history, including a full list of 1932 and 1984 Olympic gold medalists (the complete roster of honorees can be seen below).

Renovations

[edit]For many years, the Coliseum was capable of seating over 100,000 spectators. In 1964, the stadium underwent its first major renovation in over three decades. Most of the original pale green wood-and-metal bench seating was replaced by individual theater-type chairs of dark red, beige and yellow; these seats remained until 2018, although the yellow color was eliminated in the 1970s. The seating capacity was reduced to approximately 93,000.

The Coliseum was problematic as an NFL venue. At various times in its history, it was either the largest or one of the largest stadiums in the league. While this allowed the Rams and Raiders to set attendance records, it also made it extremely difficult to sell out. The NFL amended its blackout rule to allow games to be televised locally if they were sold out 72 hours before kickoff. However, due to the Coliseum's large size, Rams (and later Raiders) games were often blacked out in Southern California, even in the teams' best years.

From 1964 to the late 1970s, it was common practice to shift the playing field to the closed end of the stadium and install end zone bleachers in front of the peristyle, limiting further the number of seats available for sale. For USC–UCLA and USC–Notre Dame games, which often attracted crowds upward of 90,000, the bleachers were moved eastward and the field was re-marked in its original position. When a larger east grandstand was installed between 1977 and 1978, at the behest of Rams owner Carroll Rosenbloom, the capacity was just 71,500. With the upcoming 1984 Summer Olympic Games, a new track was installed and the playing field permanently placed inside it. However, the combination of the stadium's large, relatively shallow design, along with the presence of the track between the playing field and the stands, meant that some of the original end zone seats were as far from the field by the equivalent length of another football field. To address these and other problems, the Coliseum underwent a $15 million renovation before the 1993 football season, which included the following:[1]

- The field was lowered by 11 feet (3.4 m) and 14 new rows of seats replaced the running track, bringing the first row of seats closer to the playing field (a maximum distance of 54 feet (16.5 m) at the eastern 30-yard-line).

- A portable seating section was built between the eastern endline and the peristyle bleachers (the stands are removed for concerts and similar events).

- The locker rooms and public restrooms were "modernized."

- The bleachers were replaced with individual seating.[37]

Additionally, for Raiders home games, tarpaulins were placed over seldom-sold sections, reducing seating capacity to approximately 65,000. The changes were anticipated to be the first of a multi-stage renovation designed by HNTB that would have turned the Coliseum into a split-bowl stadium with two levels of mezzanine suites (the peristyle end would have been left as is). However, after the 1994 Northridge earthquake, the $93 million was required from government agencies (including the Federal Emergency Management Agency) to repair earthquake damage, and the renovations demanded by the Raiders were put on hold indefinitely. The Raiders then redirected their efforts toward a proposed stadium at Hollywood Park Racetrack in Inglewood before electing to move back to the Oakland Coliseum prior to the 1995 NFL season. In 2000, Bentley Management Group (BMG) was hired as the project manager to complete work at the Coliseum and Sports Arena funded by FEMA. In addition to seismically bracing the Sports Arena while it remained open for events, BMG also coordinated the Coliseum's new press box elevator, various concession stands, restroom improvements, and concrete spalling repairs.

New videoboard

[edit]In August 2011, construction began on the Coliseum's west end on a new 6,000-square-foot (560 m2) HD video scoreboard, accompanying the existing video scoreboard on the peristyle (east end) of the stadium.[38] The video scoreboard officially went into operation on September 3, 2011, at USC football's home opener versus the University of Minnesota, with the game being televised on ABC.

2018–2019 renovation project

[edit]After USC took over the Coliseum master lease in 2013, they began making plans for major renovations needed and as stipulated in the master lease agreement. On October 29, 2015, USC unveiled an estimated $270 million project for a massive renovation and restoration the Coliseum.[39] The upgrades included: replacing all seats in the stadium, construction of a larger and modern press box (with new box suites, premium lounges, a viewing deck, a V.I.P. section, and the introduction of LED ribbon boards), adding new aisles and widening some seats, a new sound system, restoration and renaming of the peristyle to the Julia and George Argyros Plaza, stadium wide Wi-Fi, two new HD video jumbotrons, new concession stands, upgraded entry concourses, new interior and exterior lighting, modernization of plumbing and electrical systems, and a reduction in capacity of about 16,000 seats, with the final total at approximately 78,500 seats.[40][41]

The plans were met with mixed reactions from the public.[42] The Los Angeles 2028 Olympic bid committee contemplated additional renovations to support its bid.[43]

On January 8, 2018, USC began the project to renovate and improve the Coliseum. The project, which was solely funded by the university, was completed by the 2019 football season, and was the first major upgrade of the stadium in 20 years.[44][16] The project budget increased from the initial estimate of $270 million to $315 million mainly due to the tight construction schedule.[5][7]

Naming rights

[edit]On January 29, 2018, Chicago-based United Airlines became the stadium's first naming rights partner.[2][12][45] Originally, Memorial Coliseum was to be retained in the name of the stadium by the condition of the Coliseum Commission's requirement in its master lease agreement with USC.[21] However, veterans groups and the new president of the Coliseum Commission raised concern about the new name,[46] while United did not approve of any change from the stadium and stated that they were willing to step away from the deal.[47]

On March 29, 2019, USC suggested the name United Airlines Field at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum instead of the planned United Airlines Memorial Coliseum. Although United also did not support this and considered withdrawal,[48] the two parties agreed to the name on June 7.[5]

During Los Angeles Rams home games for the 2019 season, the stadium reverted to its original name, and all signage indicating "United Airlines Field" was covered due to the franchise's sponsoring partnership with American Airlines.[49]

Notable events

[edit]1920s

[edit]

On October 6, 1923, Pomona and USC played in the inaugural game at the Coliseum,[50] with the Trojans prevailing 23–7. Situated just across the street from Exposition Park, USC agreed to play all its home games at the Coliseum, a circumstance that contributed to the decision to build the arena.

From 1928 to 1981, the UCLA Bruins also played home games at the Coliseum. When USC and UCLA played each other, the "home" team (USC in odd-numbered years, UCLA in even), occupied the north sideline and bench, and its band and rooters sat on the north side of the stadium; the "visiting" team and its contingent took to the south (press box) side of the stadium. Excepting the mid-1950s and 1983–2007, the two teams have worn their home jerseys for the rivalry games for the Victory Bell. This tradition was renewed in 2008, even though the two schools now play at different stadiums. UCLA moved to the Rose Bowl in Pasadena in 1982.

1930s–1940s

[edit]

In 1932, the Coliseum hosted the Summer Olympic Games, the first of two Olympic Games hosted at the stadium. The Coliseum served as the site of the field hockey, gymnastics, the show jumping part of the equestrian event, and track and field events, along with the opening and closing ceremonies.[51] The 1932 games marked the introduction of the Olympic Village, as well as the victory podium.[11]

The former Cleveland Rams of the National Football League relocated to the Coliseum in 1946, becoming the Los Angeles Rams; however, the team later relocated again, first to Anaheim in 1980, then to St.Louis in 1995, only to move back to Los Angeles in 2016. The Los Angeles Dons of the All-America Football Conference played in the Coliseum from 1946 to 1949, when the franchise merged with its NFL cousins just before the two leagues merged.[53] The Coliseum hosted the NCAA Men's Division I Outdoor Track and Field Championships in 1934, 1939, 1949, and 1955. It also hosted several Coliseum Relays and several Compton-Coliseum Invitational (track and field) events from the 1940s until the 1970s.[54]

1950s–1960s

[edit]

Among other sporting events held at the Coliseum over the years were Major League Baseball (MLB) games, which were held when the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National League relocated to the West Coast in 1958. The Dodgers played here until Dodger Stadium was completed in time for the 1962 season. Even allowing for its temporary status, the Coliseum was extremely ill-suited for baseball due to the fundamentally different sizes and shapes of football and baseball fields. A baseball field requires roughly 2.5 times more area than a football gridiron, but the playing surface was just barely large enough to accommodate a baseball diamond. As a result, foul territory was almost nonexistent down the first base line, but was expansive down the third base line, with a very large backstop for the catcher. Sight lines also left much to be desired; some seats were as far as 710 feet (216 m) from the plate. Also, from baseball's point of view, the locker rooms were huge as they were designed for football (not baseball) teams.

In order to shoehorn even an approximation of a baseball field onto the playing surface, the left-field fence was set at only 251 feet (77 m) from the plate. This seemed likely to ensure that there would be many "Chinese home runs", as such short shots were called at the time. Sportswriters began jokingly referring to the improvised park as "O'Malley's Chinese Theatre"[55] or "The House that Charlie Chan Built", drawing protests from the Chinese American community in the Los Angeles area.[56] They also expressed concern that cherished home run records, especially Babe Ruth's 1927 seasonal mark of 60, might easily fall as a result of 250-foot (76 m) pop flies going over the left-field fence. Sports Illustrated titled a critical editorial "Every Sixth Hit a Homer!"[55] Players also complained, with Milwaukee Braves ace Warren Spahn calling for a rule that would require any home run to travel at least 300 feet (91 m) before it could be considered a home run.[57]

Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick ordered the Dodgers to erect a 42 feet (12.8 m) screen in left field to prevent pop flies from becoming home runs. Its cables, towers, wires, and girders were in play.[58] The "short porch" in left field looked extremely attractive to batters. In the first week of play during the 1959 season, the media's worst preseason fears seemed to be realized when 24 home runs were hit in the Coliseum, three of them by Chicago Cubs outfielder Lee Walls, not especially distinguished as a hitter. However, pitchers soon adapted, throwing outside to right-handed hitters, requiring them to pull the bat hard if they wanted to hit toward left. Perhaps no player took better advantage than Dodgers outfielder Wally Moon, who figured out how to hit high fly balls that dropped almost vertically just behind the screen. By the end of the season, he had hit 19 homers, all but five of them in the Coliseum. In recognition, such homers were dubbed "Moon Shots".[57]

Nonetheless, the number of home runs alarmed Frick enough that he ordered the Dodgers to build a second screen in the stands, 333 ft (101 m) from the plate. A ball would have had to clear both screens to be a home run; if it cleared the first, it would have been a ground-rule double. However, the Dodgers discovered that the earthquake safety provisions of the Los Angeles building code forbade construction of a second screen.[57]

Unable to compel the Dodgers to fix the situation, the major leagues passed a note to Rule 1.04 stating that any stadium constructed after June 1, 1958, must provide a minimum distance of 325 feet (99 m) down each foul line. Also, when the expansion Los Angeles Angels joined the American League in 1961, Frick rejected their original request to use the Coliseum as a temporary facility.[59] This rule was revoked (or perhaps, simply ignored) when the Baltimore Orioles launched the "retro ballpark" era in 1992, with the opening of Oriole Park at Camden Yards. With a right field corner of only 318 feet (97 m), this fell short. However, baseball fans heartily welcomed the "new/old" style, and all new ballparks since then have been allowed to set their own distances.

Late that season, the screen figured in the National League pennant race. When the Braves were playing the Dodgers at the Coliseum on September 15, 1959, Joe Adcock hit a ball that cleared the screen but hit a steel girder behind it and got stuck in the mesh. According to ground rules, this should have been a home run. However, the umpires ruled it a ground-rule double. The fans shook the screen, causing the ball to fall into the seats. The umpires changed the call to a homer, only to rule it a ground-rule double[58] while Adcock was left stranded on second. The game was tied at the end of nine innings, and the Dodgers won in the tenth inning.[60] At the end of the regular season, the Dodgers and Braves finished in a tie. The Dodgers won the ensuing playoff and went on to win the World Series.

Although less than ideal for baseball due to its poor sight lines and short dimensions (left field at 251 feet (77 m) and power alleys at 320 feet (98 m)), the Coliseum was ideally suited for large paying crowds. Each of the three games of the 1959 World Series drew over 92,000 fans, with game five drawing 92,706, a record unlikely to be seriously threatened anytime soon given the smaller seating capacities of today's baseball parks. In May 1959, an exhibition game between the Dodgers and the New York Yankees in honor of legendary catcher Roy Campanella drew 93,103, the largest crowd ever to see a baseball game in the Western Hemisphere until a 2008 exhibition game between the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Boston Red Sox to mark the 50th anniversary of MLB in Los Angeles. The Coliseum also hosted the second 1959 MLB All-Star Game.

The Coliseum was also the site of John F. Kennedy's memorable acceptance speech at the 1960 Democratic National Convention.[61] It was during that speech that Kennedy first used the term "the New Frontier".

The Rams hosted the 1949, 1951 and 1955 NFL championship games at the Coliseum. The Coliseum was also the site of the first NFL–AFL Championship Game in 1967, an event since renamed the Super Bowl. It also hosted Super Bowl VII in 1973, but future Super Bowls in the Los Angeles region would instead be hosted at the Rose Bowl, which has never had an NFL tenant. The Coliseum was also the site of the NFL Pro Bowl from 1951 to 1972, and again in 1979. In 1960, the American Football League (AFL)'s Los Angeles Chargers played at the Coliseum before relocating to San Diego the next year; the team moved back to the L.A. area in 2017.

The United States men's national soccer team played its first match at the stadium in 1965, losing to Mexico in a 1966 World Cup qualifier. Also, the Los Angeles Wolves of the United Soccer Association played their home games at the Coliseum for a year (1967) before moving to the Rose Bowl.

1970s–1980s

[edit]In June 1970, the first Senior Olympics (known as the Senior Sports International Meet) took place at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.[62]

In July 1972, the Coliseum hosted the "Super Bowl" of Motocross. The event was the first motocross race held inside a stadium.[63] It evolved into the AMA Supercross championship held in stadiums across the United States and Canada. The Coliseum last hosted the event in 1998.[64]

On August 20, 1972, Wattstax, also known as "Black-Woodstock", took place in the Coliseum. Over 100,000 black residents of Los Angeles attended this concert for African-American pride. Later in 1973, a documentary was released about the concert.

In 1973, Evel Knievel used the entire distance of the stadium to jump 50 stacked cars. Knievel launched his motorcycle from atop one end of the Coliseum, jumping the cars in the center of the field, and stopping high atop the other end. The jump was broadcast on ABC's Wide World of Sports.[65] Also in 1973, the Coliseum was host to Super Bowl VII, which saw the AFC champion Miami Dolphins defeat the NFC champion Washington Redskins 14–7, becoming the only team in NFL history to attain an undefeated season and postseason.

The Mickey Thompson Entertainment Group hosted the first stadium short course off-road race at the Coliseum in 1979.[66] The event was last held in 1992.

The Los Angeles Rams played their home games in the Coliseum until 1979, when they moved to Anaheim prior to the 1980 NFL season. They hosted the NFC Championship Game in 1975 and 1978, in which they lost both times to the Dallas Cowboys by lopsided margins.

The Los Angeles Aztecs of the North American Soccer League used the Coliseum as their home ground in 1977 and 1981.

The Coliseum was also home to the USFL's Los Angeles Express between 1983 and 1985. In this capacity, the stadium also is the site of the longest professional American football game in history: on June 30, 1984 (a few weeks before the start of the 1984 Summer Olympics), a triple-overtime game between the Express and the Michigan Panthers that was decided on a 24-yard game-winning touchdown by Mel Gray of the Express, three and a half minutes into the third overtime, to give Los Angeles a 27–21 win. Until 2012, this game marked the only time in the history of professional football that there was more than one kickoff in overtime play in the same game.[67]

In 1982, the former Oakland Raiders moved in. The same year, UCLA decided to move out, relocating its home games to the Rose Bowl in Pasadena.

The Coliseum was also the site of the 1982 Speedway World Final, held for the first and only time in the United States. The event saw Newport Beach native Bruce Penhall retain the title he had won in front of 92,500 fans at London's Wembley Stadium in 1981. An estimated 40,000 fans were at the Coliseum to see Penhall retain his title before announcing his retirement from motorcycle speedway to take up an acting role on the television series CHiPs.

Los Angeles hosted the 1984 Summer Olympics, and the Coliseum became the first stadium to host the Summer Olympic Games twice, again serving as the primary track and field venue and as the site of the opening and closing ceremonies.[68]

The Coliseum played host to the California World Music Festival on April 7–8, 1979.[69]

The Rolling Stones played at the stadium on their 1981 Tattoo You tour (October 9 and 11),[70] supported by George Thorogood, the J. Geils Band, and Prince. Relatively unknown at the time, Prince was not well-received by fans and booed off the stage the first night. He did not intend to return for the second show until convinced by Stones frontman Mick Jagger to do so.[71] The Stones played for 90,000 for each of 2 nights in 1981 and a record 90,000 fans for 4 nights in 1989.

The Argentina national soccer team played a friendly match against Mexico on May 14, 1985,[72] as part of Argentina's tour of North America prior to the 1986 FIFA World Cup that would be won by the squad managed by Carlos Bilardo.

Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band concluded their Born in the U.S.A. Tour with four consecutive concerts on September 27, 29, 30, and October 2, 1985, in front of 82,000 people each night. These shows were recorded and eight songs from the show of September 30 appear on their box set Live 1975–85. The September 27 show was released through Springsteen's website in 2019.

U2 played at the stadium during leg three of their breakout Joshua Tree tour on November 17 and 18, 1987. They later returned to the stadium for their PopMart Tour on June 21, 1997.

Los Angeles natives Mötley Crüe played at the stadium on December 13, 1987, during the second leg of their Girls, Girls, Girls World Tour, with fellow Los Angeles band Guns N' Roses as the opening act. At that time, Mötley Crüe was one of the most popular and successful acts in the world, while Guns N' Roses was one of the largest up-and-coming acts. The latter would later return for four shows in October 1989 as the opening act for the Rolling Stones, then again on September 27, 1992, as part of their infamous co-headlining tour with Metallica.

The stadium played host to The Monsters of Rock Festival Tour, featuring Van Halen, Scorpions, Dokken, Metallica, and Kingdom Come, on July 24, 1988. A second show was planned to take place on July 23, but was later canceled.

The stadium also played host to Amnesty International's Human Rights Now! Benefit Concert on September 21, 1988, headlined by Sting and Peter Gabriel and also featuring Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Tracy Chapman, Youssou N'Dour, and Joan Baez.

1990s–2000s

[edit]The Raiders began looking to move out of the Coliseum as early as 1986. In addition to the delays in renovating the stadium, they never drew well; even after they won Super Bowl XVIII in 1984, they had trouble filling it. The NFL scheduled all of the Raiders' appearances on Monday Night Football as road games since the Los Angeles market would have been blacked out due to the Coliseum not being sold out. Finally, in 1995, the Raiders left Los Angeles and returned to Oakland, leaving the Coliseum without a professional football tenant for the first time since the close of World War II.

In the mid-1990s, the Coliseum was planned to be the home of the Los Angeles Blaze, a charter franchise of the United League (UL) which was planned to be a third league of Major League Baseball.

In 2000, the Los Angeles Dragons of the Spring Football League used the Coliseum as their home stadium.

The Legends Football League began as a halftime spectacular known as the Lingerie Bowl. The first three years (2004, 2005, 2006) were played at the Coliseum. From 2009 to 2011, a couple of Los Angeles Temptation games were played in the Coliseum. Beginning in 2015, the Temptation resumed playing at the Coliseum after three seasons at Citizens Business Bank Arena in Ontario.

The 1991 CONCACAF Gold Cup soccer tournament was also held at the Coliseum. The United States national team beat Honduras in the final. The Coliseum also staged the final match of the Gold Cup in 1996, 1998 and 2000. In October 2000, the United States played its last match at the stadium in a friendly versus Mexico. Since then, the team has preferred the Rose Bowl Stadium and Dignity Health Sports Park as home stadiums in Greater Los Angeles.

The stadium hosted the K-1 Dynamite!! USA mixed martial arts event. The promoters claimed that 54,000 people attended the event, which would have set a new attendance record for a mixed martial arts event in the United States; however, other officials estimated the crowd between 20,000 and 30,000.[73]

In May 1959, the Dodgers had hosted an exhibition game against the reigning World Series champion New York Yankees at the Coliseum, a game which drew over 93,000 people. The Yankees won that game 6–2. As part of their West Coast 50th anniversary celebration in 2008, the Dodgers again hosted an exhibition game against the reigning World Series champions, the Boston Red Sox.[74] On March 29, 2008, the middle game of a three-game set in Los Angeles was also won by the visitors by the relatively low score of 7–4, given the layout of the field; Red Sox catcher Jason Varitek had joked that he expected scores in the 80s.

As previously mentioned in the 1950s–1960s section, during 1958–1961, the distance from home plate to the left field foul pole was 251 feet (76.5 m) with a 42-foot (13 m) screen running across the close part of left field. Due to the intervening addition of another section of seating rimming the field, the 2008 grounds crew had much less space to work with, and the result was a left field foul line only 201 ft long (61.3 m), with a 60-foot (18 m) screen, which one Boston writer dubbed the "Screen Monster".[75] Even at that distance, 201 feet (61 m) is also 49 ft (14.9 m) short of the minimum legal home-run distance. This being an exhibition game, balls hit over the 60 ft (18 m) temporary screen were still counted as home runs. There were only a couple of home runs over the screen, as pitchers adjusted (and Manny Ramirez did not play).[76] A diagram ([77]) illustrated the differences in the dimensions between 1959 and 2008:

- 2008 – LF 201 ft (61.3 m) – LCF 280 ft (85.3 m) – CF 380 ft (115.8 m) – RCF 352 ft (107.3 m) – RF 300 ft (91.4 m)

- 1959 – LF 251 ft (76.5 m) – LCF 320 ft (97.5 m) – CF 417 ft (127.1 m) – RCF 375 ft (114.3 m) – RF 300 ft (91.4 m)

A sellout crowd of 115,300 was announced,[78] which set a Guinness World Record for attendance at a baseball game, breaking the record set at a 1956 Summer Olympics baseball demonstration game between teams from the US and Australia at the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

The Coliseum formerly hosted the major U.S. electronic dance music festival, the Electric Daisy Carnival. It last hosted the event in 2010; following the drug-related death of an underage attendee at EDC that year, the festival's organizer Insomniac Events was blacklisted from hosting future events at the venue, and it subsequently moved to Las Vegas Motor Speedway in 2011.[79][80][81][82][83]

In 2003, select events of the X Games IX action sports event were held at the Coliseum. In 2010, the X Games XVI were held at the venue.[64]

In 2006, the Coliseum Commission focused on signing a long-term lease with USC, who offered to purchase the facility from the state but was turned down. After some at-time contentious negotiations, with the university threatening to move to the Rose Bowl in late 2007, the two sides signed a 25-year lease in May 2008, giving the Coliseum Commission 8% of USC's ticket sales, approximately $1.5 million a year, but committing the agency to a list of renovations.[84]

In 2006, Mexican band RBD held a concert during their U.S. tour before 70,000 people, with tickets sold out in less than 30 minutes. It was the highest attended event by a Mexican act since Los Bukis' 1993 and 1996 concerts.[85]

On June 23, 2008, the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission announced that they were putting the naming rights of the Coliseum on the market, predicting a deal valued at $6 million to $8 million a year.[84] The funds would go towards financing over $100 million in renovations over the next decade, including a new video board, bathrooms, concession areas, and locker rooms.[84] Additional seating was included in the renovation plans which increased the Coliseum's seating capacity to 93,607 in September 2008.[86][87]

On June 17, 2009, the Coliseum was the terminus for the Los Angeles Lakers' 2009 NBA championship victory parade. A crowd of over 90,000 attended the festivities, in addition to the throngs of supporters who lined the 2-mile (3.2 km) parade route. The Coliseum peristyle was redesigned in purple and gold regalia to commemorate the team, and the Lakers' court was transported from Staples Center to the Coliseum field to act as the stage. Past parades had ended at Staples Center, but due to the newly constructed L.A. Live complex, space was limited around the arena.[88]

2010s–present

[edit]

On July 30, 2011, the LA Rising festival with Rage Against the Machine, Muse, Rise Against, Lauryn Hill, Immortal Technique, and El Gran Silencio was hosted at the Coliseum.

Roger Waters continued his The Wall Live at the stadium on 19 May 2012 to a sold-out crowd.

On April 27, 2013, the stadium hosted a round of the Stadium Super Trucks off-road race.

On September 13, 2014, the Coliseum hosted the fifth-place game, third-place game and final of the 2014 Copa Centroamericana in front of 41,969 spectators.

In August 2015, the Coliseum hosted the opening and closing ceremonies for the 2015 Special Olympics World Summer Games.[89]

On June 16, 2018, Shannon Briggs hosted the first press conference for a celebrity boxing event with KSI, Deji, Jake Paul, and Logan Paul.[90]

On September 14, 2021, the NASCAR Cup Series announced that the annual Busch Clash would take place at the Coliseum, at a purpose-made quarter-mile track.[91]

On December 9, 2021, Kanye West performed a benefit concert for the long-imprisoned Larry Hoover with special guest Drake at the Coliseum.

On September 23 and 24, 2022 German band Rammstein performed two shows as part of the North American leg of their Rammstein Stadium Tour

On December 10, 2022, Deadmau5 and Kaskade performed as their collaborative project Kx5 to a crowd of 50,000. Making it the largest ever one-day EDM headlining event in North America at the time.

Return of the Los Angeles Rams 2016–19

[edit]

On January 12, 2016, the NFL gave permission for the St. Louis Rams to relocate back to Los Angeles. The Rams resumed play at the Coliseum while awaiting completion of SoFi Stadium in Inglewood.[92][93]

On August 13, 2016, the Coliseum hosted its first NFL game at the stadium since 1994, as the Rams hosted the Dallas Cowboys at a preseason game in front of 89,140 people. On September 18, 2016, the Coliseum hosted the first Rams regular season home game since 1979, against the Seattle Seahawks following an impromptu pregame concert from the Red Hot Chili Peppers. The Rams would boast a 9–3 victory over Seattle in front of a crowd of 91,046 in attendance.

On January 6, 2018, the Coliseum hosted its first Rams playoff game since the 1978 NFC Championship game, a 26–13 wild card round loss to the defending NFC champion Atlanta Falcons.

On November 19, 2018, the Coliseum hosted its first Monday Night Football game since 1985, and the first Monday night game the Rams hosted at the Coliseum, exact date 40 years later, with the Rams taking on the Kansas City Chiefs. That game, which was originally scheduled to be played at Estadio Azteca in Mexico City that night, was moved to the Coliseum due to poor field conditions at the former. The Rams won the game, 54–51 in the highest-scoring game in Monday Night Football history.

On January 12, 2019, the Coliseum hosted its final NFL playoff game, where the Rams defeated the Dallas Cowboys 30–22 in an NFC Divisional Playoff.

On December 8, 2019, the final Sunday Night Football game would be played at the Coliseum in which the Rams defeated the rival Seattle Seahawks 28–12 in front of a crowd of over 77,000 people.

On December 29, 2019, the Rams played their final game at the Coliseum, beating the Arizona Cardinals 31–24 before moving to SoFi Stadium in time for the 2020 NFL season. The Rams finished with a record of 16–14 playing their home games at the Coliseum in their second stint as tenants from 2016 through 2019.

On February 16, 2022, three days after winning Super Bowl LVI, the Rams hosted their victory celebration before thousands of fans in front of the Coliseum's peristyle end.

2028 Summer Olympics

[edit]Los Angeles will host the Summer Olympics in 2028.[94] During the 131st IOC Session, the International Olympic Committee officially awarded the 2028 Summer Olympics to Los Angeles on July 31, 2017.[95][96] The Coliseum will be the first stadium to host events for three different Olympic games.[12]

NASCAR

[edit]On February 6, 2022, NASCAR hosted a pre-season NASCAR Cup Series exhibition event. The temporary .25-mile (402-meter) track marked the series' first race of any kind on a quarter-mile since 1971 and was won by Joey Logano. Martin Truex Jr. won the 2023 running of the event, followed by Denny Hamlin in 2024. The event was moved to Bowman Gray Stadium in 2025.[97]

Seating and attendance

[edit]

Seating capacity (college football)

[edit]| Years | Capacity |

|---|---|

| 1930 | 75,144 |

| 1934 | 101,574 |

| 1939 | 105,000 |

| 1946 | 103,000 |

| 1947–1964 | 101,671 |

| 1965–1966 | 97,500 |

| 1967–1975 | 94,500 |

| 1976–1982 | 92,604 |

| 1983–1995 | 92,516 |

| 1996–2007 | 92,000 |

| 2008–2017 | 93,607 |

| 2018 | 78,500 |

| 2019–present | 77,500 |

- Source:Ballparks.com[98]

Attendance records

[edit]1963 Billy Graham Crusade

[edit]The largest gathering in the Coliseum's history was a Billy Graham crusade which took place on September 8, 1963, with 134,254[99] in attendance, noted by the Coliseum's website as an all-time record. With the renovations of 1964, the capacity of the Coliseum was reduced to roughly 93,000 for future events.

Sporting events

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

- College football

Records differ between the 2006 USC football media guide and 2006 UCLA football media guide. (This may be due to only keeping records for "home" games until the 1950s.) The USC Media guide lists the top five record crowds as:

- 1. 104,953 — vs. Notre Dame 1947 (USC home game; Highest attendance for a football game in the Coliseum)

- 2. 103,303 — vs. UCLA 1939 (USC home game)

- 3. 103,000 — vs. USC 1945 (UCLA home game)

- 4. 102,548 — vs. USC 1954 (UCLA home game)

- 5. 102,050 — vs. UCLA 1947 (USC home game)

The UCLA Media guide does not list the 1939 game against USC, and only lists attendance for the second game in 1945 for Coliseum attendance records. These are the top three listed UCLA record Coliseum crowds:

- 1. 102,548 — vs. USC 1954 (UCLA home game)

- 2. 102,050 — vs. USC 1947 (UCLA home game)

- 3. 100,333 — vs. USC 1945 (USC home game; 1945's second of two meetings)

The largest crowd to attend a USC football game against an opponent other than UCLA or Notre Dame was 96,130 for a November 10, 1951, contest with Stanford University. The largest attendance for a UCLA contest against a school other than USC was 92,962 for the November 1, 1946, game with Saint Mary's College of California.

- National Football League

The Los Angeles Rams played the San Francisco 49ers before an NFL record attendance of 102,368 on November 10, 1957. This was a record paid attendance that stood until September 2009 at Cowboys Stadium, though the overall NFL regular season record was broken in a 2005 regular season game between the Arizona Cardinals and San Francisco 49ers at Azteca Stadium in Mexico City.[100][101] Both records were broken on September 20, 2009, at the first regular season game at Cowboys Stadium in Arlington, Texas, between the Dallas Cowboys and New York Giants.

In 1958 the Rams averaged 83,680 for their six home games, including 100,470 for the Chicago Bears and 100,202 for the Baltimore Colts.

In their 13 seasons in Los Angeles the Raiders on several occasions drew near-capacity crowds to the Coliseum. The largest were 91,505 for an October 25, 1992, game with the Dallas Cowboys, 91,494 for a September 29, 1991, contest with the San Francisco 49ers, and 90,380 on January 1, 1984, for a playoff game with the Pittsburgh Steelers.

The Coliseum hosted the first AFL–NFL World Championship Game, later called the Super Bowl. The January 15, 1967, game, pitting the Green Bay Packers against the Kansas City Chiefs, attracted 61,946 fans—a lower-than anticipated crowd (by comparison, a regular-season game between the Packers and Rams a month earlier drew 72,418). For Super Bowl VII in 1973, which matched the Miami Dolphins against the Washington Redskins, the attendance was a near-capacity 90,182, a record that would stand until Super Bowl XI at the Rose Bowl. The 1975 NFC Championship Game between the Los Angeles Rams and Dallas Cowboys had an attendance of 88,919, the highest for an NFC Championship Game. The 1983 AFC Championship Game between the Raiders and Seattle Seahawks then attracted 91,445, still the largest crowd for a conference championship game since the conference-title format began with the 1970 season.

The Rams' first NFL game at the Coliseum since 1979, after spending fifteen years at Anaheim Stadium and then twenty-one seasons in St. Louis, a pre-season contest against the Cowboys on August 13, 2016, drew a crowd of 89,140. The team's first regular-season home game, on September 18 against the Seattle Seahawks, attracted 91,046—the largest attendance for a Rams game at the Coliseum since 1974.

- Major League Baseball

Contemporary baseball guides listed the theoretical baseball seating capacity as 92,500. Thousands of east-end seats were very far from home plate, and were not sold unless needed. The largest regular season attendance was 78,672, the Dodgers' home debut in the Coliseum, against the San Francisco Giants on April 18, 1958.

The May 7, 1959, exhibition game between the Los Angeles Dodgers and the 1958 World Series Champion New York Yankees, in honor of disabled former Dodgers catcher Roy Campanella, drew 93,103, which was a Major League Baseball record prior to 2008.

All three Dodgers home games in the 1959 World Series with the Chicago White Sox exceeded 90,000 attendance. Game 5 drew 92,706 fans, a major league record for a non-exhibition game.

The attendance for the exhibition game on March 29, 2008, between the Boston Red Sox and the Los Angeles Dodgers, was 115,300,[102] setting a new Guinness World Record for attendance at a baseball game. The previous record of an estimated 114,000 was in the 1956 Summer Olympics at Melbourne Cricket Ground for an exhibition game between teams from branches of American Military Forces and Australia.

- Soccer

The first official soccer match at the Coliseum was an international fixture between the United States and Mexico that took place on March 7, 1965, as part of regional World Cup qualification. The teams drew 2–2 in front of 22,570 spectators.[103]

Although the stadium represents the second most active venue in the history of the US national team (after Robert F. Kennedy), it has only played 22 matches in it, the last of them in 2000. Of these, eleven were of official competition (three from World Cup qualifiers, seven from the CONCACAF Gold Cup and one from the North American Nations Cup) and eleven friendlies, all category "A". In this scenario, the team won their first absolute title by finishing as champion of the 1991 CONCACAF Gold Cup, defeating their counterpart from Honduras on penalties.[104]

However, the most active national team at the Memorial Coliseum is Mexico, which has played 86 matches in the building: 14 in official competition (3 in the World Cup qualifying round, 9 in the Gold Cup and two from the North American Nations Cup), including the Gold Cup finals from 1996 and 1998, in which they won 2–0 against Brasil and 1–0 against United States respectively; and 72 friendlies (50 of Category "A" – against other senior teams – 6 of the so-called "B" selection and 16 against both Mexican and foreign clubs). Los Angeles is the second stadium where the Mexican representative has played the most matches, only after its official headquarters, the Azteca Stadium, surpassing any other venue both in his country and in the United States.[105]

The stadium hosted the Los Angeles Wolves during the inaugural season of the United Soccer Association in 1967, which culminated in the final championship at the Coliseum. The Los Angeles Toros of the National Professional Soccer League also played at the Coliseum in 1967, but were moved to San Diego the following season before folding.[106] The Los Angeles Aztecs of the North American Soccer League played at the Coliseum in 1977 and 1981 between stints at the Rose Bowl.[107]

Sculpture and commemorations

[edit]A pair of life-sized bronze nude statues of male and female athletes atop a 20,000-pound (9,100-kilogram) post-and-lintel frame formed the Olympic Gateway created by Robert Graham for the 1984 games. The statues, modeled on water polo player Terry Schroeder[108] and several women, [Jane Frederick of Santa Barbara, an Olympic pentathlete who did not qualify for the games] and a long jumper from Guyana, Jennifer Inniss, who participated in the games, were noted for their anatomical accuracy. A decorative facade bearing the Olympic rings was erected in front of the peristyle for the 1984 games, and the structure remained in place through that year's football season. The stadium rim and tunnels were repainted in alternating pastel colors that were part of architect Jon Jerde's graphic design for the games; these colors remained until 1987.

Court of Honor plaques

[edit]"Commemorating outstanding persons or events, athletic or otherwise, that have had a definite impact upon the history, glory, and growth of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum"[109]

- 1959 Dodgers World Series, 1961

- 1963 Billy Graham Crusade,[110] 1965

- 50th Anniversary of Armistice, 1969

- John C. Argue, 2004

- Count Baillet-Latour, 1964

- Elgin Baylor, 2009

- Joan Benoit, 2017

- Thomas Bradley, 2019

- Judge William A. Bowen, 1955

- Coliseum Commission – 1984 Olympics, 1984

- Coliseum Commission (1933–1944), 1970

- Coliseum Commission (1945–1970), 1970

- Coliseum Commission (1971–1998), 1998

- Coliseum Commission Restoration (1923), 2013

- Coliseum Track and Field Records, 2002

- Community Development Association, 1932

- Pierre de Coubertin, 1958

- Newell "Jeff" Cravath, 1960

- Dean Bartlett Cromwell, 1963

- Anita DeFrantz, 2017

- Mildred "Babe" Didrickson, 1961

- Earthquake Restoration, 1999

- John Ferraro, 2000

- John Jewett Garland, 1972

- William May Garland, 1949

- Kenneth F. Hahn, 1993

- Elmer "Gus" Henderson, 1971

- Paul Hoy Helms, 1958

- Elroy "Crazy Legs" Hirsch, 2005

- Rafer Johnson, 2009

- Thomas LaBonge, 2022

- Israeli Olympic Athletes, 1984

- Pope John Paul II, 1987

- Howard Harding Jones, 1955

- President John F. Kennedy, 1964

- Francis "Frank" Leahy, 1974

- Nelson Mandela, 2014

- James Francis Cardinal McIntyre and Mary's Hour, 1966

- John McKay, 2001

- Mercy Bowl, 1961

- J.D. Morgan, 1984

- Jesse P. Mortensen, 1963

- Jim Murray, 1999

- William Henry "Bill" Nicholas, 1990

- Walter F. O'Malley, 2008

- James Cleveland "Jesse" Owens, 1984

- Charles W. Paddock, 1955

- Rams Reunion, 2007

- Daniel Farrell Reeves, 1972

- Jackie Robinson, 2005

- Knute Rockne, 1955

- Pete Rozelle, 1998

- Henry Russell "Red" Sanders, 1959

- W.R. "Bill" Schroeder,[111] 1990

- Vin Scully, 2008

- Andrew Latham "Andy" Smith, 1956

- William Henry "Bill" Spaulding, 1971

- Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, 2016

- Amos Alonzo Stagg, 1965

- Brice Union Taylor, 1975

- USC All-Americans (1880–2005), 2007

- Peter V. Ueberroth, 2022

- Glenn Scobey "Pop" Warner, 1956

- Kenneth Stanley Washington, 1972

- Jerry West, 2009

- John R. Wooden, 2008

- Rosalind Wyman, 2021

Coliseum Cauldron

[edit]The Coliseum Cauldron was built for the 1932 Summer Olympics and was also reused during the 1984 Summer Olympics. The cauldron is a main sight on stadium and is still present in the Stadium and is lit during special events (such as the period when an edition of the Olympic Games are being held in another city or in mourning for some personality related to the city). As the stadium was the main venue on the 2015 Special Olympics World Summer Games the cauldron was relit by Rafer Johnson during the opening ceremonies and being extinguished again during the closing ceremony.

In addition, the torch has been lit on the following historic occasions:

- To honor the memory of Israeli athletes killed during the terrorist attack during the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich.

- For several days following the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986.

- For over a week following the September 11 attacks in 2001.

- The pyre was lit for a week without interruption during the official period of mourning after the death of the former American president Ronald Reagan. Reagan was the president of the United States when the city of Los Angeles hosted the 1984 Summer Olympics and also declared that edition of the Games open, and was also Governor of California from 1967 to 1975.

- In April 2005 following the death of Pope John Paul II, who had celebrated Mass at the Coliseum during his visit to Los Angeles in 1987.

- At the Los Angeles Dodgers' 50th anniversary game on March 29, 2008, during the ThinkCure! charity ceremony (while Neil Diamond's "Heartlight" was played and the majority of the attendees turned on their complimentary souvenir keychain flashlights).

- For the returning Los Angeles Rams' first home game on September 18, 2016, against the Seattle Seahawks.

- On the evening of September 13, 2017, when Los Angeles was awaiting a few hours before the confirmation as the host city of the 2028 Summer Olympics.

- For the Coliseum Gladiator MMA Championship Finals on Sat., September 23, 2017.

- For the Los Angeles Rams' first playoff game in Los Angeles in 38 years on January 6, 2018, against the Atlanta Falcons.

- To honor the victims of the 2018 California wildfires & the Thousand Oaks shooting.

- For the Los Angeles Rams' final regular season game against the San Francisco 49ers on December 30, 2018.

- For the Los Angeles Rams' playoff game against the Dallas Cowboys on January 12, 2019.

- For the Rams' final game in the Coliseum vs. the Arizona Cardinals on December 29, 2019.

- To honor Kobe Bryant after his death on January 26, 2020.

- To honor Rafer Johnson after his death on December 2, 2020.

- To honor former L.A. Councilman Tom LaBonge, known to many as "Mr. Los Angeles" after his death on January 14, 2021.[112]

- To honor Dodgers Legend Tommy Lasorda after his death on January 14, 2021.

- For the Kanye West and Drake Larry Hoover Benefit Concert on December 9, 2021.

- For the 2022 NASCAR Busch Light Clash at the Coliseum on February 6, 2022. The Cauldron was ceremoniously lit by 4 time NASCAR Champion Jeff Gordon.

- After the death of Mexican singer Vicente Fernandez on February 17, 2022. The artist had performed at the LA Memorial Sports Arena various times.

- For the 2023 NASCAR Busch Light Clash at the Coliseum, the Cauldron was lit by 2022 Heisman Trophy winner Caleb Williams.

- Since May 1, 2023 the Cauldron has been ceremoniously lit the first of each month to commemorate the centennial of the venue's lasting legacy and influence on Los Angeles and the world.

- On November 1, 2024 during the Los Angeles Dodgers Victory parade to commemorate the Dodgers eighth World Series Championship.[113]

In popular culture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2020) |

Film

[edit]- 1923: Scenes from the Roman Age in Buster Keaton's Three Ages were filmed in the Coliseum, the first ever use of the Coliseum as a movie location.

- 1927: Scenes in College a 1927 comedy-drama silent film directed by James W. Horne and Buster Keaton, and starring Keaton, Anne Cornwall, and Harold Goodwin are filmed on the field of the Coliseum.

- 1944: Scenes in “The Falcon in Hollywood” starring Tom Conway.

- 1972: The Coliseum was used in the filming of Hickey & Boggs. There is a gunfight that takes place within the stadium.

- 1976: The Coliseum was the key location in the movie Two-Minute Warning.

- 1978: The Coliseum was used in the filming of Warren Beatty's film Heaven Can Wait, about a fictional Super Bowl XII game between the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Los Angeles Rams.

- 1994: The outside of the Coliseum was used as a scene in D2: The Mighty Ducks.

- 1996: The Coliseum was used in the filming of Escape from L.A. starring Kurt Russell, including a basketball death match.

- 1997: The Coliseum was used in the filming of Money Talks starring Chris Tucker and Charlie Sheen.

- 2002: The field and locker room were used in the filming of the pornographic Gangbang Girl #32 starring Kimberly Franklin, Olivia Saint and Gauge[114][115][116]

- 2013: The stadium appears in one of the final scenes of World War Z when the military bombs the stadium full of zombies.[117]

Television and streaming

[edit]- 1972: The Coliseum was a key location in "The Most Crucial Game", the third episode of the second season of Columbo.

- 1976: The Coliseum was used in filming of Emergency! (1970's TV Series) episode titled "The Game".

- 1978: The Coliseum was used in the filming of The Incredible Hulk episode titled "Killer Instinct".

- 1978: The Coliseum was used in the filming of the Charlie's Angels episode titled "Pom Pom Angels".

- 2003: The Coliseum was used in the filming of the last episode of the second season of the television series 24.[118]

- 2008: The Coliseum was used as the starting point of the premiere episode of The Amazing Race 13.[119]

- 2009: The Coliseum was featured in Life After People. 150 years after people, an earthquake brings down the Coliseum.

- 2016: The Coliseum was used as the finishing point for the second episode of the Chinese reality show Race the World.[120]

- 2019: Season 17 of Bravo's Top Chef filmed an episode at the Coliseum at the 1923 Club on the roof of the new Scholarship Club Tower.[121]

- Visiting... with Huell Howser Episode 411, which includes an interview of Robert Graham.[122]

- 2021: The Coliseum was used in the filming of the last episode of the fifth season of the Netflix series Lucifer.

Video games

[edit]- 1996: Microsoft Flight Simulator for Windows 95 included a challenge to fly through the needle of the Coliseum and land on the field.[123]

- 2004/2013: The Maze Bank Arena featured in Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas and Grand Theft Auto V has an outer wall and arch similar to the Coliseum, but has a roof.[124]

- 2005: The Coliseum is featured as one of the playable Supercross tracks in MX vs. ATV Unleashed .

- 2008: The Coliseum was featured in Midnight Club: Los Angeles, albeit with a different name.

- 2011: The Coliseum featured as a rallycross track in Dirt 3.

- 2014: The Coliseum is one of the main settlements of Los Angeles in Wasteland 2.

- 2019: The Coliseum is featured as one of the playable Supercross tracks in Monster Energy Supercross 2: The Official Video Game as a DLC.

See also

[edit]- BMO Stadium

- List of NCAA Division I FBS football stadiums

- History of the National Football League in Los Angeles

- Lists of stadiums

People

- A.J. Barnes, active in fight against giving USC preferential rights in the Coliseum, 1932

- Lloyd G. Davies, Los Angeles City Council member, 1943–51, urged that the city take over full management of the Coliseum

- Harold A. Henry, Los Angeles City Council president and later a member of the Coliseum Commission

- Rosalind Wiener Wyman, first representative of the Los Angeles City Council on the Coliseum Commission, 1958

- Ransom M. Callicott, Los Angeles City Council, commission member, 1962

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Memorial Coliseum". University of Southern California. 2009. Archived from the original on March 2, 2010. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- ^ a b Thiry, Lindsey - USC Trojans' home is now officially the United Airlines Memorial Coliseum. Los Angeles Times, January 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Benson, Michael (1989). Ballparks of North America: a comprehensive historical reference to baseball grounds, yards, and stadiums, 1845 to present. McFarland. ISBN 0-89950-367-5.

- ^ a b 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c "The University of Southern California and United Airlines Agree to Field Naming". USC Trojans. June 7, 2019. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- ^ "USC kicks off $270 million renovation of Coliseum - USC News. January 29, 2018". USC News. January 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Kaufman, Joey (May 31, 2018). "USC's Coliseum renovation about $30 million over budget". Orange County Register. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ^ "General FAQs". welcomehomerams.com. Los Angeles Rams. January 18, 2016. Archived from the original on January 17, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

Where will the Rams play? For the first three seasons we'll play at the L.A. Coliseum. In 2019, we'll move into the most advanced, world-class stadium ever built located in Inglewood, CA.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ Charleton, James H. (June 21, 1984). "Los Angeles Memorial.Coliseum" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places – Inventory Nomination Form. National Park Service. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ a b c Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Archived November 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, National Landmarks Program, National Park Service, Accessed November 12, 2007.

- ^ a b c Mackovich, Ron (January 29, 2018). "United Airlines Memorial Coliseum to be new name for L.A. landmark". USC News.

- ^ a b "USC Auxiliary Services". USC Auxiliary Services.

- ^ "USC and United Airlines agree to name field at the Coliseum". USC News. June 7, 2019.

- ^ Kalbrosky, Bryan (December 6, 2016). "Don't judge Rams home attendance based on percentage of seats filled". Rams Wire. Gannett Co., Inc.

- ^ a b "The USC Coliseum Renovation Project Website". Archived from the original on February 26, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ "Coliseum renovation reaches halfway point with topping-off ceremony". USC News. August 15, 2018.

- ^ "USC, L.A. leaders reintroduce the renovated Coliseum". USC News. August 15, 2019.

- ^ "Renovation Unveiled at Iconic Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum". DLR Group. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission > About Us". lamcc.lacounty.gov.

- ^ a b "Second Amendment to Lease and Agreement by and between the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission and University of Southern California effective July 29, 2013". www.lamcc.lacounty.gov.

- ^ "LA Coliseum Employment".

- ^ Sam Farmer, Coliseum panel mulls options, Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2007.

- ^ USC to take over L.A. Coliseum, Sports Arena on Monday LATimes

- ^ [1], "Board approves Coliseum lease". ESPN. June 26, 2013.

- ^ [2], "USC signs historic lease agreement with LA Coliseum" September 5, 2013

- ^ "Second Amendment to Lease and Agreement By and Between Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission and University of Southern California" (PDF). July 29, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 26, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ "LA Memorial Coliseum Completes $315M Renovation Ahead Of Football Season". August 15, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ "RESTORING A CLASSIC: THE L.A. COLISEUM – Los Angeles Coliseum". August 8, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ [3], " Trojans Women Soccer team Battle With No. 1 Bruins at LA Coliseum"

- ^ [4], "LA Memorial Coliseum & Sports Arena Booking Information"

- ^ "A commencement two years in the making begins: Classes of 2020 and 2021 walk the Coliseum stage". May 14, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "Update on 2025 USC Commencement". September 6, 2024. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ "Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum". Los Angeles Conservancy. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ "Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum". Archived from the original on October 19, 2006.

- ^ Dwyre, Bill (July 28, 2009). "The 1984 Olympics had Rafer Johnson to light the way". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ Stadiums of the NFL-Los Angeles Coliseum-Los Angeles Rams/Raiders Archived February 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "USC Official Athletic Site – USCTrojans.com". www.usctrojans.com.

- ^ "USC PROPOSES ESTIMATED $270-MILLION RENOVATION PLAN FOR LA COLISEUM". ABC 7 Los Angeles. October 29, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ "USC Official Athletic Site – USCTrojans.com". www.usctrojans.com.

- ^ "Preserving an Icon for Future Victories". DLR Group. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "Coliseum renovation a hot topic among USC Trojans faithful". ESPN.com. November 2, 2015.

- ^ "LA Coliseum To Undergo Major Renovations For Olympic Bid". August 25, 2015.

- ^ Kaufman, Joey (January 8, 2018). "USC-driven construction starts on renovations to Coliseum". Orange County Register. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ "United Gets L.A. Coliseum Naming Rights In College-Record Deal". www.sportsbusinessdaily.com. May 18, 2017.

- ^ "Vets Aren't Happy That LA Memorial Coliseum Will Take A Corporate Name In August". Colorado Public Radio. May 22, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ Gerber, Marisa (March 31, 2019). "The $69-million Coliseum naming-rights deal between USC and United is in limbo". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ "United Airlines offers to withdraw from Coliseum naming rights deal with USC". AP. March 29, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2019 – via Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Rich Hammond (August 24, 2019). "So when the Rams play here, it's not United Airlines Field". twitter.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ "U.S.C. plays Pomona". Berkeley Daily Gazette. California. October 6, 1923. p. 7.

- ^ 1932 Summer Olympics official report. Archived April 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine pp. 61–8.

- ^ "Patton and Doolittle". Los Angeles Coliseum.

- ^ James P. Quirk and Rodney D. Fort, Pay Dirt: The Business of Professional Team Sports, p. 438, ISBN 0-691-01574-0

- ^ LA84, Track and Field Meet Results c1964. [5] Retrieved Oct. 31, 2020

- ^ a b McCue, Andy (2014). Mover and Shaker: Walter O'Malley, the Dodgers, and Baseball's Westward Expansion. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 221–22. ISBN 9780803255050. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ Szalontai, James D. (2002). Close Shave: The Life and Times of Baseball's Sal Maglie. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 356. ISBN 9780786411894. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c Schwarz, Alan (March 26, 2008). "201 Feet to Left, 440 Feet to Right: Dodgers Play the Coliseum". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Lowry, Phillip (2005). Green Cathedrals. New York City: Walker & Company. ISBN 0-8027-1562-1.

- ^ Purdy, Dennis (2006). The Team-by-Team Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. New York City: Workman. ISBN 0-7611-3943-5.

- ^ "Milwaukee Braves at Los Angeles Dodgers Box Score, September 15, 1959 - Baseball-Reference.com". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ Sahagun, Louis (April 14, 2019). "Supervisor Janice Hahn and presidential candidate Tulsi Gabbard oppose Coliseum name change". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ San Bernardino County Sun, June 23, 1970. [6] Retrieved Oct. 29, 2020

- ^ "The First Supercross". motorcyclistonline.com. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- ^ a b A Coliseum of dirt - Brian Kamenetzky, ESPN, 28 July 2010

- ^ "ABC Sports – Wide World of Sports". ESPN. Archived from the original on December 7, 2002.

- ^ Craig Peronne (July 16, 2013). "Back to the Future". Four Wheeler.

- ^ Michigan Panthers Archived January 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine USFL.info

- ^ 1984 Summer Olympics official report. Archived November 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Volume 1. Part 1. pp. 72–9.

- ^ California World Music Festival Poster.

- ^ The Rolling Stones American Tour 1981

- ^ "The Rolling Stones with Prince". Los Angeles Coliseum.

- ^ ARGENTINA NATIONAL TEAM ARCHIVE by Héctor Pelayes on the RSSSF

- ^ Springer, Steve (June 3, 2007). "Morton doesn't last one round". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Hernandez, Dylan (November 14, 2007). "Dodgers to play host to Red Sox in March". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008.

- ^ "Coliseum configuration confounding", March 29, 2008, MLB.com. Retrieved on November 10, 2012.

- ^ MLB803093, USAToday.com.

- ^ [7], LAtimes.com

- ^ 6195168.story, LAtimes.com.

- ^ "'EDC' Raver Teen Sasha Rodriguez Died From Ecstasy Use". LA Weekly. August 31, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ "A fatal toll on concertgoers as raves boost cities' income". Los Angeles Times. February 3, 2013.

- ^ "Man dies at Electric Daisy Carnival in Las Vegas". Chicago Tribune. June 22, 2014.

- ^ Jon Pareles (September 1, 2014). "A Bit of Caution Beneath the Thump". New York Times.

- ^ "Electric Zoo to Clamp Down on Drugs This Year". Wall Street Journal. August 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c Futterman, Matthew (June 24, 2008). "Landmark's Name Is up for Sale". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- ^ "The Coliseum History". Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ Distribution, Media-Newswire.com – Press Release. "Media-Newswire.com – Press Release Distribution – PR Agency". media-newswire.com.

- ^ www.dailytrojan.com Archived September 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Blankstein, Andrew (June 18, 2009). "Lakers parade goes off mostly without a hitch". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Carly Rae Jepsen, O.A.R. and Andra Day to Headline the LA2015 Special Olympics World Games Closing Ceremony on August 2". specialolympics.org. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- ^ "Logan Paul and KSI Nearly Come to Blows at Superfight News Conference". TMZ. June 16, 2018. Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- ^ Bianchi, Jordan. "NASCAR's 2022 schedule shakes up playoff tracks, adds Gateway in June: Sources". The New York Times. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Hanzus, Dan (January 12, 2016). "Rams to relocate to L.A.; Chargers first option to join". NFL.com. National Football League. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "Rams to Return to Los Angeles". St. Louis Rams. January 12, 2016. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "LA 2028". www.la28.org.

- ^ Wharton, David (July 31, 2017). "Details emerge in deal to bring 2028 Summer Olympics to Los Angeles". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "IOC MAKES HISTORIC DECISION BY SIMULTANEOUSLY AWARDING OLYMPIC GAMES 2024 TO PARIS AND 2028 TO LOS ANGELES". Olympic.org. September 13, 2017.

- ^ Albert, Zack (August 17, 2024). "Season-opening Clash exhibition heads to Bowman Gray Stadium in 2025". Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ "Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum". www.ballparks.com.

- ^ "Coliseum History | LA Coliseum". www.lacoliseum.com. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ Weir, Tom (October 3, 2005). "Cardinals deep-six 49ers in historic tilt in Mexico". USA Today.

Total attendance for record regular season game in Mexico City Azteca Stadium is 103,467 breaking the record of 102,368 who saw the Rams play the 49ers on Nov. 10, 1957, at the Los Angeles Coliseum

- ^ Weir, Tom (September 25, 2005). "Mexico gets ready for football, not futbol". USA Today.

A 1994 Houston-Dallas exhibition drew a still-standing NFL record 112,376 to Estadio Azteca

- ^ "Boxscore: Boston vs. LA Dodgers - March 29, 2008". Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- ^ "U.S. Fortunate to Gain Mexican Soccer Standoff". Los Angeles Times. March 8, 1965. p. 1. Retrieved August 2, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dave Litterer. "USA - International Results". RSSSF.

- ^ "Mexico - International Results". RSSSF.

- ^ Digiovanna, Mike (January 22, 1986). "Gaining A Foothold". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ Baker, Chris (January 31, 1981). "Aztecs Are Going Back to Coliseum". Los Angeles Times. p. 8. Retrieved August 2, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Crowe, Jerry (December 11, 2006). "Schroeder learns to grin and bare the naked truth". Los Angeles Times. Crowe's nest column. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ "Memorial Court of Honor, List of Honoree Plaques" on the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum website

- ^ "The Coliseum History". Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ Benedict, Chuck (January 14, 2000). "I guess I missed it. Surely, there must have been an all-century list of sports' most influential personalities". Glendale New-Press. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ "Former L.A. Councilman Tom LaBonge, known to many as 'Mr. Los Angeles,' dies at 67". Los Angeles Times. January 8, 2021.

- ^ https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2024-10-31/dodgers-championship-landmarks-celebrate-blue

- ^ Kovacik • •, Robert (May 31, 2012). "Porn Filmed on Grounds of Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum".

- ^ Snow, Aurora (May 31, 2012). "Aurora Snow: Inside the L.A. Coliseum Porno". The Daily Beast – via www.thedailybeast.com.

- ^ "Internet Adult Film Database". www.iafd.com.

- ^ "Cruise missile strike on football stadium (World War Z film)". YouTube. October 19, 2013.

- ^ Steve Richardson, 24 Reasons to Shoot in LA Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, California Film Industry Magazine, Accessed June 19, 2007.

- ^ "The Amazing Race 13: Meet the Cast". IGN. August 19, 2008. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Bingqiao, Zhou (April 21, 2016). "《非凡搭档》洛杉矶制片手记" ["Race the World" Los Angeles Production Notes]. Sina (in Chinese). Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Here's Your First Look at the History-Making Top Chef Season 17 All Stars L.A." Bravo TV Official Site. February 11, 2020.

- ^ "L.A. Coliseum – Visiting (411) – Huell Howser Archives at Chapman University". December 7, 2016.

- ^ "Microsoft Flight Simulator for Windows 95 (Game)".

- ^ Bell, David Christopher (September 25, 2013). "Sightseeing San Andreas: 8 Real World Movie Locations You Can Find In GTA 5". Film School Rejects. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission – operated by Los Angeles County

- Los Angeles Sports Council Archived May 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- USC Trojans.com – L.A. Memorial Coliseum

- Sanborn map showing the Coliseum, 1954

- Image of a white woman waving from a palanquin carried by Black men at a shrine pageant at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, 1935. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Summer Olympics Opening and closing ceremonies venue (Olympic Stadium) 1932 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by Olympisch Stadion

Amsterdam |

Summer Olympics Athletics competitions Main venue 1932 |

Succeeded by Olympiastadion

Berlin |