Tamara Bunke

Tamara Bunke | |

|---|---|

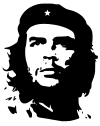

Bunke in 1962 wearing the tilted beret of the newly formed Cuban People's Defence Militia | |

| Born | Haydée Tamara Bunke Bider November 19, 1937 Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Died | August 31, 1967 (aged 29) Vallegrande Province, Bolivia |

| Cause of death | Killed in action |

| Resting place | Che Guevara Mausoleum Santa Clara, Cuba |

| Nationality | East German Argentine Cuban Bolivian |

| Occupation(s) | Communist revolutionary East German/Cuban spy Journalist |

| Organization | National Liberation Army |

Haydée Tamara Bunke Bider (November 19, 1937 – August 31, 1967) was an Argentine-born East German revolutionary known for her involvement in feminism, leftist politics, and liberation movements.

Born to communist parents, Bunke joined the Free German Youth at fifteen and later studied philosophy at university. She was recruited as an interpreter for the Socialist Unity Party of Germany, where she met Che Guevara during his visit to Leipzig. In 1961, she moved to Cuba and participated in the Cuban literacy campaign and Federation of Cuban Women.

Bunke was recruited for Bolivian Campaign, Che Guevara's guerrilla expedition in Bolivia aimed at sparking revolution across Latin America. Using the alias Tania, she infiltrated Bolivian high society and developed ties with Bolivian President René Barrientos.

In 1966, her cover was blown, leading her to join Guevara's armed guerrilla campaign in Bolivia. During this time, she was responsible for the food and monitoring radio communications. Bunke was killed in 1967 during an ambush by Bolivian Army Rangers while attempting to escape with a leg injury and fever.

Early life

[edit]Born in November 1937 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Tamara Bunke was the daughter of Erich Bunke and Nadia Bider.[1][2] Nadia Bider Bunke, born in 1912, was a Russian communist who hailed from a Jewish family within the Russian Empire. Her father, Erich Bunke, relocated to Berlin at the age of 18 to pursue studies in architecture. Both Nadia and Erich took part in left-wing politics; however due to Nazi persecution, they were forced to flee to Argentina in 1935.[3] Erich faced persecution for his involvement with the Communist Party of Germany, while Nadia, being of Jewish descent, also became a target of persecution.[4]

Erich Bunke and Nadia Bider secured positions as teachers upon their arrival in Argentina.[5] Shortly thereafter, they became members of the Communist Party of Argentina, ensuring that Tamara and her brother Olaf would both grow up in a Marxist-Leninist political atmosphere. Their family home in Buenos Aires was often used for meetings, helping communist refugees, hiding publications and occasionally stashing weapons.[6] In 1952, after the end of World War II, the family came back to the newly created East Germany, specifically Eisenhüttenstadt.[7]

Tamara played multiple musical instruments, including the piano, guitar, and accordion, with special interest in Latin American's folk music.[7] By the age of fourteen, she joined the ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany's (SUPG) youth organization, the Free German Youth (FGY) and by eighteen, she joined the SUPG.[6] In addition, she also joined the World Federation of Democratic Youth, allowing her to attend the World Festival of Youth and Students in Vienna, Prague, Moscow and Havana.[8]

Bunke commenced her studies in philosophy[9] or political science,[6] depending on the source, at Humboldt University in East Berlin, where she distinguished herself due to her linguistic skills; she was fluent in English, Spanish, French and German.[6][9] Bunke soon began working as a translator of several Latin American leaders during their visits to East Germany, particularly those associated with the FGY's International Relations Department.[10]

Cuba

[edit]

After the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro dispatched emissaries to various socialist countries to garner support. In this capacity, in 1960, Che Guevara was sent to Leipzig, East Germany, as part of a Cuban trade delegation. Bunke was assigned to accompany him as his interpreter.[1][9] Subsequently, in 1961, she received an invitation from Alicia Alonso to travel to Cuba.[11][12]

She first worked as an interpreter for the Cuban National Ballet. She also involved herself in voluntary work, namely teaching and participating in the construction of homes and schools in rural areas.[9] As a result, she participated in work brigades, the militia, and the Cuban Literacy Campaign.[13] She also worked in the Ministry of Education, the Cuban Institute for Friendship Among People, and the Federation of Cuban Women, where she made close ties with Vilma Espín.[13] Additionally, she registered for a journalism degree at the University of Havana.[13]

Tamara worked for the Asociación de Jóvenes Rebeldes, later known as the Union of Young Communists. She assisted in organizing an international student union conference in Havana. Tamara also joined the People's Defense Militia and collaborated with various Latin American individuals who sought solidarity with their struggles, including Nicaraguan revolutionary Carlos Fonseca. She actively participated in the insurgency in Nicaragua, establishing connections with members of the Sandinista National Liberation Front.[14]

Dámaso Tabares was entrusted with the task of selecting a compañera for Operation Fantasma in Bolivia. Three candidates were considered, and Tamara was eventually chosen for training to participate in Che Guevara's guerrilla expedition. Guevara's goal was to spark a continent-wide revolutionary uprising into neighboring Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil, Peru, and Chile.[9][13]

In preparation, Guevara assigned Bunke to be trained by Dariel Alarcón Ramírez.[9] It was during this period that she took the name "Tania" as her nom de guerre in honor of Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, a Soviet partisian who also used this alias.[13] Between 1963 and 1964, she underwent training, culminating in a period of instruction in Prague, where she received training from the StB. It was during this training that she formed a romantic relationship with Dámaso Tabares.[15]

Bolivian insurgency

[edit]

In October 1964, Bunke traveled to Bolivia under the name Laura Gutiérrez Bauer, as a secret agent for Guevara's last campaign. Her first mission was to gather intelligence on Bolivia's political elite and the strength of its armed forces.[9] Posing as a right-wing folklore expert of Argentine background, she quickly found herself infiltrating high society and rubbing shoulders with the glitterati of Bolivia's academic and official circles.[13][16] Showing how high she was able to rise in La Paz society, she won the adoration of Bolivian President René Barrientos, and even went on holiday with him to Peru.[9] In order to maintain her cover, she also busied herself part-time with her explorations of folk music (producing one of the most valuable collections of Bolivian music in the process) and entered into a fraudulent marriage of convenience with a young Bolivian to gain citizenship.[9][13]

In late 1966 however, Bunke travelled to their rural camp at Ñancahuazú on a number of occasions. On one of these trips, a captured Bolivian communist gave away a safe house where Tania's jeep was parked in which she had left her address book. As a result, her cover was blown, and she now had no other choice than to join Guevara's armed guerrilla campaign. She helped with rationing food and monitoring radio broadcasts.[13] Fellow surviving guerrilla Benigno, said that Bunke and Guevara had at some point become lovers in Bolivia; with Benigno remarking decades later in 2008 that "You could tell by the way they spoke so quietly and looked at each other when they were together near the end".[9]

Without Bunke as the guerrilla's contact to the outside world, the guerrillas then found themselves isolated. Bunke also soon found herself battling a high fever, a leg injury and the painful effects of the Chigoe flea parasite.[9][13] Consequently, Guevara decided to try to send a group of 16 other ailing combatant, out of the mountains.[9][13]

Death

[edit]"Will my name one day be forgotten

and nothing of me remain on the Earth?"

— Tamara Bunke, a 1966 poem[9]

Following Tania's rise to prominence in Bolivia she became too easily identifiable, so Che initiated arrangements for her departure. On April 17, a detachment led by Juan Vitalio Acuña Núñez departed from the main guerrilla force due to injuries and illness, which included Tania. Guided by Honorato Rojas, a Bolivian peasant, the group was led to the location where Bolivian soldiers were strategically positioned and concealed.[17][18]

At 5:20 pm on August 31, 1967, the lead guerrilla column was ambushed while crossing the Río Grande at Vado del Yeso.[9] Tania was in the water, when she was shot in the arm and lung and killed along with eight of the insurgents.[9][19] Her body was then carried downstream and only recovered by the Bolivian Army seven days later on September 6. Her corpse was supposedly transferred by helicopter to Vallegrande. Days later when her corpse was presented to Barrientos, it was decided that it would be buried in an unmarked grave with the rest of the guerrillas. However, the local campesino women said she be given a proper Christian burial.[20]

On September 7, when her death was announced over the radio, Guevara, still struggling through the jungles close by, refused to believe the news; suspecting it was army propaganda to demoralize him. Later, when Fidel Castro learned of her demise, he declared "Tania the guerrilla" a hero of the Cuban Revolution.[9]

After the research of biographer Jon Lee Anderson led to the discovery of Che Guevara's remains in 1997, Bunke's remains were also tracked down to an unmarked grave in a small pit on the periphery of the Vallegrande army base on October 13, 1998. They were transferred to Cuba and were interred in the Che Guevara Mausoleum in the city of Santa Clara, alongside those of Guevara himself and several other guerrillas killed during the Bolivian insurgency.[21][22]

Controversies

[edit]Since the time of her death there have been reports that she was a triple agent working for the Soviet KGB, the East German Stasi and for the Cuban intelligence; along with the claim that she and Che Guevara were lovers while in Bolivia and that she may have even been carrying his child when she was killed;[9] this was finally refuted in 2017 by Dr. Abraham Baptista, who was in charge of the autopsy of both Ché and Tamara Bunke.[23]

Before Nadia Bunke died in 2003, she also managed to have the book Tania, the Woman Che Guevara Loved by Uruguayan author José A Friedl, removed from sale in Germany.[13] German courts ruled that the book contained defamatory allegations against Tamara Bunke; namely Friedl repeated Stasi defector Günter Männel's rumor from the 1970s that Bunke and Guevara started an extramarital affair in 1965 while training together in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic's capital of Prague.[9][13] However, although they both did receive instruction by the StB in Prague, they were never in the city at the same time.[13]

Popular culture

[edit]Following Bunke's death, the media swiftly sought to reduce her to merely Che Guevara's romantic partner, thus diminishing her contributions to the Bolivian Campaign.[24] Certain intellectuals associated her as a femme fatale, whose death was due to her extramarital affair with Che.[13] Soviet-Ukrainian astronomer Lyudmila Zhuravleva named a minor planet discovered in 1974, 2283 Bunke, in her honour.[25] Bunke has been depicted in numerous films, songs, and theatrical productions, most notably, portrayed by Franka Potente in the film Che.[26][27][28][29] In fiction literature and games, Tamara's presence is equally notable.[30][31][32] Additionally, during Patty Hearst's involvement with the Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974, she adopted the alias "Tania."[33]

Further reading

[edit]- Tania: Undercover With Che Guevara in Bolivia, by Ulises Estrada, Ocean Press (AU), 2005, ISBN 1-876175-43-5

- Henderson, James D., Linda R. (1978). Ten notable women of Latin America. pp. 213–240. OCLC 641752939.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Mother Fights Che Film Over 'Lover' Claims by Tony Paterson & Oliver Poole, Daily Telegraph, March 17, 2002

- ^ Estrada 2005a, pp. 149

- ^ "Lives in Brief". The Times. 2024-03-15. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ Estrada 2005a, pp. 149

- ^ "BUNKE, Tamara – | Diccionario Biográfico de las Izquierdas Latinoamericanas". diccionario.cedinci.org. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ a b c d "Tamara Bunke: espía y guerrillera a las órdenes del 'Che'". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 2021-07-11. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ a b Estrada 2005a, pp. 24

- ^ Estrada 2005a, pp. 151–152

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Haydée Tamara Bunke Bider: the woman who died with Che Guevara[dead link] by Christine Toomey, The Sunday Times, August 10, 2008

- ^ Estrada 2005a, pp. 23

- ^ "Tamara Bunke: la compañera de armas del "Che" Guevara". Muy Interesante (in Mexican Spanish). 2019-03-07. Retrieved 2024-03-17.

- ^ Estrada 2005b, pp. 153

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Tania: Undercover with Che Guevara in Bolivia Archived 2020-10-20 at the Wayback Machine A Book Review by Bob Briton, The Guardian, January 26, 2005

- ^ Estrada 2005b, pp. 24–26

- ^ Estrada 2005a

- ^ Tania: Undercover with Che Guevara in Bolivia, by Ulises Estrada, 2005, Ocean Press, ISBN 1-876175-43-5

- ^ "Muerte del grupo de "Joaquín" en Bolivia - 5 Septiembre" (in Spanish). 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ Estrada 2005a, pp. 120–121

- ^ Estrada 2005a, pp. 121–122

- ^ Estrada 2005a, pp. 125–126

- ^ Brown, Jonathan C. (2017-10-01). "What Happened to the People Behind the Assassination of Che Guevara?". History News Network. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ Estrada 2005a, pp. 134

- ^ ""Es hora de decir cómo murió el Che" - Proceso" (in Mexican Spanish). 2017-10-09. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- ^ Moser, Caroline O. N. (2023-09-19). "'Che' and Tania's socks: Bolivian recollections of an 'incorporated wife'". Women's History Review. 32 (6): 887–900. doi:10.1080/09612025.2023.2193487. ISSN 0961-2025.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 186. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

- ^ Che: Part Two (2008) - IMDb, retrieved 2024-03-14

- ^ Muskus, Zetty; Vásquez, Jorge (2004). Los personajes en las canciones de Alí Primera. Colección de literatura. Trujillo] : [Caracas?] : [Trujillo: Fondo Editorial Arturo Cardozo ; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deportes, Viceministerio de Cultura, Consejo Nacional de Cultura ; Gobierno Bolivariano del Edo. Trujillo. ISBN 978-980-376-077-9.

- ^ Stenzl, Jürg (1995). "Prometeo—Tragedia dell'ascolto". Paris Lodron University of Salzburg.

- ^ "Heidi Specogna Biography". swissfilms. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ https://www.anderson.ucla.edu/faculty_pages/sebastian.edwards/Capital%20Entrevista%20Tanias.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Griffin, W. E. B. (2001). Special Ops. Putnam's. ISBN 978-0-399-14646-6.

- ^ Pfarrer, Chuck (2007). Killing Che. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6393-2.

- ^ Radeska, Tijana (2017-07-29). "Patty Hearst took the name "Tania" from a 1960s Communist revolutionary in Bolivia who mastered the art of disguise | The Vintage News". thevintagenews. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

Bibliography

[edit]- Estrada, Ulises (2005a). Tania: undercover with Che Guevara in Bolivia. Internet Archive. Melbourne [Australia] : New York : Ocean Press. ISBN 978-1-876175-43-6.

- Estrada, Ulises (2005b). Tania la guerrillera: y la epopeya suramericana del Che. Internet Archive. Melbourne ; Nueva York : Ocean Press. ISBN 978-1-920888-21-3.

External links

[edit]- Images of Tania

- Members of Che Guevara's Guerrilla Movement in Bolivia – by the Latin American Studies Organization

- Female revolutionaries

- 1937 births

- 1967 deaths

- People from Buenos Aires

- Anti-revisionists

- Argentine communists

- Argentine Jews

- Argentine revolutionaries

- Cuban spies

- East German spies

- Socialist Unity Party of Germany politicians

- Women in war in South America

- Argentine people of German-Jewish descent

- Argentine people of Polish-Jewish descent

- Che Guevara

- Guerrillas killed in action

- Deaths by firearm in Bolivia

- Women in war 1945–1999

- Argentine emigrants

- Immigrants to East Germany

- University of Havana alumni

- East German women

- People from Bezirk Frankfurt

- Female guerrillas