Lydia Koidula

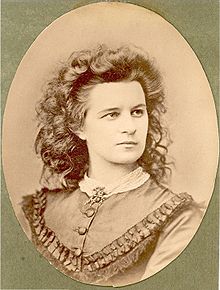

Lydia Michelson (Koidula) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Lydia Emilie Florentine Jannsen 24 December 1843 |

| Died | 11 August 1886 (aged 42) Kronstadt, Russian Empire |

| Occupations | |

| Spouse |

Eduard Michelson (m. 1873) |

| Children | 3 |

| Family | Johann Voldemar Jannsen (father) |

Lydia Emilie Florentine Michelson (née Jannsen; 24 December [O.S. 12 December] 1843 – 11 August [O.S. 30 July] 1886), known by her pen name Koidula, was an Estonian writer and journalist. She is now considered the national poet by Estonians and frequently referred to as Koidulaulik – 'Singer of the Dawn' in Estonian.

In Estonia, like elsewhere in Europe, writing was not considered a suitable career for a respectable young lady in the mid-19th century. Koidula's early poetry and her works published in the newspapers edited by her father Johann Voldemar Jannsen (1819–1890, a leader of the Estonian national awakening) remained mostly anonymous. In spite of this, she was a major literary figure and also became a founder of the Estonian-language theatre. She was in close communication with Carl Robert Jakobson (1841–1882, an influential radical Estonian nationalist) and Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (1803–1882, author of the Estonian national epic, Kalevipoeg). Over time, she has achieved the status of the national poet of Estonia.[1]

Biography

[edit]

Lydia Jannsen was born in Vändra (Fennern), Estonia. The family moved to the nearby county town of Pärnu (Pernau) in 1850 where, in 1857, her father started publishing an Estonian-language weekly regional newspaper Pärnu Postimees and where she attended the German-language grammar school. The Jannsens moved to the university town of Tartu (Dorpat) in 1864. Any kind of expression of nationalism, including publication in indigenous languages, was a sensitive subject in the Russian Empire, however the rule of Czar Alexander II (1855–1881) was relatively liberal and Jannsen managed to persuade the imperial censorship to allow him to publish the first Estonian-language newspaper with nationwide distribution in 1864.[2] Both the Pärnu regional and the national newspaper were called Postimees ('The Courier'). Lydia Jannsen wrote for her father in both papers besides publishing her own work.

In 1873, she married Eduard Michelson, an army physician, and moved to Kronstadt (naval base near Saint Petersburg, then capital of the Russian Empire). In 1876–1878, the Michelsons visited Breslau, Strasbourg and Vienna. Lydia Michelson lived in Kronstadt for 13 years and albeit during that time she would spend the summers in Estonia, she reportedly never stopped feeling inconsolably homesick.

Lydia Michelson was mother of three children. She died from breast cancer on 11 August 1886, at age 42. Her last poem was Enne surma — Eestimaale! ('Before death, to Estonia!').

Works

[edit]Koidula's most important work, Emajõe ööbik, ('The Nightingale of River Emajõgi'), was published in 1867.[2] Three years earlier, in 1864, Adam Peterson, a farmer, and Johann Köler, an Estonian portraitist living in Saint Petersburg, had petitioned the emperor for better treatment from the German landowners who ruled the Baltic provinces, equality, and for the language of secondary and higher education to be Estonian instead of German. Immediately afterwards they were taken to the police where they were interrogated about a petition that 'included false information and was directed against the state'. Peterson was sentenced to imprisonment for a year. Two years later, in 1866, the censorship reforms of 1855 that had given Koidula's father a window to start Postimees were reversed. Pre-publication censorship was re-imposed and literary freedom was curtailed. This was the political and literary climate when Koidula started to publish. Nevertheless, it was also the time of the national awakening when most Estonian people started to feel pride in their ethnic identity and to aspire to self-determination. Koidula was the most articulate voice of these aspirations.

German influence in Koidula's work was unavoidable.[3] The local German-speaking nobility had retained hegemony in the region since the 13th century and German was the main language of tuition, and of the intelligentsia, in 19th century Estonia. Like her father (and all other Estonian writers at the time) Koidula translated much sentimental German prose, poetry and drama and there is a particular influence of the Biedermeier movement. Biedermeier, a style which dominated 'bourgeois' art in continental Europe from 1815 to 1848, developed in the wake of the suppression of revolutionary ideas following the defeat of Napoleon. It was plain, unpretentious and characterised by pastoral romanticism; its themes were the home, the family, religion and scenes of rural life. The themes of Koidula's early Vainulilled (Meadow Flowers; 1866) were certainly proto-Biedermeier, but her delicate, melodic treatment of them was in no way rustic or unsophisticated, as demonstrated in the unrestrained patriotic outpourings of Emajõe Ööbik. Koidula reacted to the historical subjugation of the Estonian people as to a personal affront; she spoke of the yoke of serfdom and subordination as if from personal experience. By the start of the "Estonian Age of Awakening" in the 1850s, her country had been ruled by foreign powers and the local German landowners for over 600 years. In this context, she was conscious of her own role in the destiny of the nation. She once wrote to a Finnish correspondent: "It is a sin, a great sin, to be little in great times when a person can actually make history".

The Estonian literary tradition started by Kreutzwald continued with Koidula. Whereas Kreutzwald tried to imitate the regivärss folk traditions of ancient Estonian, Koidula wrote mostly in modern, Western European end-rhyming metres that had, by the mid 19th century, become the dominant form. This made Koidula's poetry much more accessible to the popular reader. But the major importance of Koidula lay not so much in her preferred form of verse but in her potent use of the Estonian language. Estonian was, in the 1860s, still a far less prestigious language in a German dominated Baltic province of Imperial Russia. Printed Estonian was still a subject of orthographical bickering, used most of the time for patronising educational or religious texts, practical advice to farmers or cheap and cheerful popular story telling. Koidula successfully used the vernacular language to express emotions that ranged from an affectionate poem about the family cat, in Meie kass ('Our Cat') and delicate love poetry, Head ööd ('Good Night') to a powerful cri de coeur and rallying call to an oppressed nation, Mu isamaa nad olid matnud ('My Fatherland, They Have Buried'). With Koidula, the German supremacist view that the Estonian language was an underdeveloped instrument for communication was, for the first time, demonstrably contradicted.

Drama

[edit]Koidula is also considered the "founder of Estonian theatre" through her drama activities at the Vanemuine Society (Estonian: Vanemuise Selts), a society started by the Jannsens in Tartu in 1865 to promote Estonian culture.[4] Lydia was the first to write original plays in Estonian and to address the practicalities of stage direction and production. Despite some Estonian interludes at the German theatre in Tallinn, in the early 19th century, there had been no appreciation of theatre as a medium and few writers considered drama of any consequence, though Kreutzwald had translated two verse tragedies. In the late 1860s, both Estonians and Finns started to develop performances in their native tongues and Koidula, following suit, wrote and directed the comedy, Saaremaa Onupoeg ('The Cousin from Saaremaa') in 1870 for the Vanemuine Society. It was based on Theodor Körner's (1791–1813) farce Der Vetter aus Bremen, ('The Cousin from Bremen') adapted to an Estonian situation.[5][6] The characterisation was rudimentary and the plot was simple, it was popular and Koidula went on to write and direct Maret ja Miina, (aka Kosjakased; 'The Betrothal Birches', 1870) and her own creation, the first ever completely Estonian play, Säärane mulk ('What a Bumpkin!'). Koidula's attitude to the theatre was influenced by the philosopher, dramatist, and critic Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729–1781), the author of Erziehung des Menschengeschlechts ('The Education of the Human Race'; 1780). Her plays were didactic and a vehicle for popular education. Koidula's theatrical resources were few and raw – untrained, amateur actors and women played by men – but the qualities that impressed her contemporaries were a gallery of believable characters and cognizance of contemporary situations.

Commemoration

[edit]

At the first Estonian Song Festival, in 1869, an important rallying event of the Estonian patriots, two poems were set to music with lyrics by Lydia Koidula: Sind surmani ('Till Death') and Mu isamaa on minu arm ('My Fatherland is My Love'). The latter became the unofficial anthem during the 1944–1991 Soviet occupation when her father's Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm ('My Fatherland, My Happiness and Joy') — the official national anthem of the Republic of Estonia — was forbidden. Koidula's song always finished every Song Festival, with or without permission from authorities of the then Soviet-occupied country. The tradition has continued to this day.[7]

A branch of the Pärnu Museum gives an overview of the life and work of poet Lydia Koidula and her father Johann Voldemar Jannsen. The Koidula museum is located in a former shool building (constructed in 1850, with unique interior of the era). It was the home of Johann Voldemar Jannsen and the editorial office of his Perno Postimees newspaper until 1863. The building is now under protection as a historical landmark. Jannsen's elder daughter, poet Lydia Jannsen (better know by her pen name Koidula) grew up in the house. It is the main task of the museum to keep alive their memory and to introduce their life and work in the context of the period of national awakening in Estonia through the permanent exposition.[8][9]

There is a monument of Koidula in the city center of Pärnu next to the building of the historical Victoria Hotel on the corner of Kuninga and Lõuna streets. The monument dates to 1929 and was the last work by Estonian sculptor Amandus Adamson.[10] Koidula was depicted on the Estonian 100 krooni banknote, in circulation from 1992 until replaced by euros in 2011.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ Richard C. Frucht (2005). "Estonia". Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. Vol. I. ABC-Clio. p. 91. ISBN 1-57607-800-0.

- ^ a b Gunter., Faure (2012). The Estonians : the long road to Independence. Mensing, Teresa. London: Lulu.com. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-1105530036. OCLC 868958072.

- ^ "Estonica.org - Baltic German literature and its impact". www.estonica.org. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ^ "Ljubov Vassiljeva, The Origins of Theatre in Estonia – Mirek Kocur". kocur.uni.wroc.pl. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ^ Johnson, Jeff (2007). The new theatre of the Baltics : from Soviet to Western influence in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. p. 93. ISBN 9780786429929. OCLC 76786725.

- ^ "Theatre Vanemuine - Teater Vanemuine". Teater Vanemuine. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ^ Jaworowska, Jagna. "Revolution by Song: Choral Singing and Political Change in Estonia". enrs.eu (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2018-08-02. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ^ Taylor, Neil (2002). Estonia (3rd ed.). Chalfont St. Peter, England: Bradt. p. 180. ISBN 9781841620473. OCLC 48486870.

- ^ "Koidula Museum". www.parnumuuseum.ee. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ^ Indrek, Rohtmets (2006). A cultural guide to Estonia : travel companion. Liivamägi, Marika,, Randviir, Tiina. Tallinn. p. 59. ISBN 9789985310441. OCLC 183186590.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lestal, Tania (2017-07-16). "Estonia - Paradise of the North: Lydia Koidula & the 100 kroon Estonian banknote". Estonia - Paradise of the North. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ots.L. The History of Estonian Literature. University of Tartu.

- Olesk.S & Pillak.P . Lydia Koidula .24.12.1843-11-08.1886. Tallinn. Umara Kirjastus, P.14

- Nirk.E. Estonian Literature. Tallinn Perioodika. 1987. pp73–77, 79–81, 366

- Raun.T.U. Estonia and the Estonians. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford. 2001. pp 77–79, 188

- Kruus.O & Puhvel.H. Eesti kirjanike leksikon. Eesti raamat.Tallinn. 2000. pp 210– 211